A new employee may be joining your workplace soon – the drone pilot.

“Pilot” may seem like a grandiose name for someone who operates a gadget the size of a toaster, but the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) considers them pilots with responsibilities similar to those of pilots who fly in their aircraft. In fact, a large and increasing body of law closely regulates drones and their pilots.

This matters to employers. When an employee flies a drone on behalf of her employer, the employer may be held responsible for her violation of these laws and any damages she causes. To reduce these risks, companies using drones should implement a comprehensive policy to regulate their use. Drone pilots may not wear pilot’s caps and stripes on their shoulders, but that is all the more reason for the employer to make sure that they are aware of, and comply with, their piloting responsibilities.

Workplace Drones Are Increasing

Drones have already entered many workplaces. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reports that the commercial drone fleet now numbers about 100,000 drones and predicts that this number will increase five-fold to a half million commercial drones by 2021.

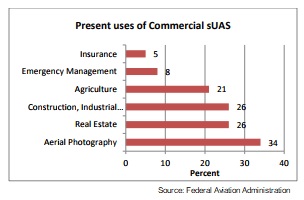

For now, drone use tends to be clustered in a few industries. Agribusiness has found that drones can efficiently collect a wide range of information in real time about agricultural conditions, such as water use and heat signatures. The construction business uses drones to quickly survey sites and monitor progress. Large retailers are adopting drone technology to manage inventory. For example, Wal-Mart has tested drones to find missing items in its warehouses.

Drones have quickly become an essential technology for  photography services: movie studios use them to collect stunning aerial footage; real estate companies rely on drones for 360 degree views of properties; and, increasingly, drones buzz around corporate events and weddings to get the perfect shot.

photography services: movie studios use them to collect stunning aerial footage; real estate companies rely on drones for 360 degree views of properties; and, increasingly, drones buzz around corporate events and weddings to get the perfect shot.

Drones have steadily made inroads into other industries too: the oil and gas industry to check remote pipelines; the insurance industry to inspect properties; fire-fighting departments to track fires — the list goes on and on. Many businesses are finding that drones are a cheap and efficient way to extend their reach without putting employees in harm’s way.

Your Business May Already Be Flying

Don’t be surprised to discover that drones are already in your workplace. Due to the explosion of interest in hobbyist drones, the initiative for a company’s drone program often comes bottom up from employees. In 2016, the FAA estimated that Americans owned about one million hobbyist drones. This is not a passing fad. The FAA expects the number to triple to 3.6 million by 2021.

After learning how to fly the drones at home, it’s natural for employees to realize drones could make their jobs easier and then bring them to work.

How Employers Can Be Held Responsible

Regardless of whether the initiative for drone use in the workplace comes top down from management or bottom up from workers, drones flown on behalf of the company can expose the company to legal risk.

A common misconception among employers is that the employer cannot bear responsibility for actions taken by employees without the company’s permission or knowledge. That is not the case. Under the legal doctrine of “respondeat superior,” or “the master answers,” a company can potentially be held liable for actions of employees that fall within the scope of employment and are motivated, at least partially, by a purpose to serve the employer.

Of course, the employer is more likely to bear liability for the acts that it directs, but many employers have been found liable for unauthorized employee actions.

Laws Regulating Drones

An employee’s use of a drone for company business can lead to liability for the employer both under traditional causes of action, such as negligence and invasion of privacy, and also under a growing number of laws drafted specifically to regulate drones.

The most comprehensive of the latter are the regulations issued in 2016 by the FAA. The FAA’s regulations treat drones much like manned aircraft. They set out the precise air space in which drones may operate and add strict limitations specific to drones. For example, the FAA regulations prohibit drones from flying beyond the visual line of sight of the pilot.

Just as drones are regulated like aircraft, drone pilots must meet criteria similar to that of conventional pilots. Drone pilots must be vetted by the Transportation Security Administration, obtain a remote pilot certificate with a small unmanned aerial system rating, and be free of any mental or physical condition that could interfere with safe drone operation.

Failure to comply with the FAA’s regulations could result in an enforcement action and a fine. In early 2017, the FAA announced a $200,000 settlement with SkyPan International, Inc., a company specializing in aerial photography. SkyPan had allegedly violated FAA regulations by flying drones in congested airspace over New York and Chicago.

States May Also Regulate Drones

Drone operators must also contend with a growing number of state drone laws. For example, in Florida, the Unmanned Aircraft Systems Act prohibits flying a drone near “critical infrastructure,” which includes cell phone towers, electrical power plants, and natural gas storage facilities. Texas has a similar restriction. In addition, Texas prohibits, with some exceptions, using a drone to conduct surveillance over private real estate. The owner of the property can win statutory damages of $5,000 for a single episode.

Texas is not alone in passing legislation to protect privacy from drones. As another example, a statute in Oregon provides a legal cause of action for real property owners against a drone operator who flies over their property after being asked to stop.

Even in states without privacy laws specific to drones, drone operators face privacy risks. Every state provides some form of legal protection for privacy. Drones can easily run afoul of these protections. Most drones carry some form of a camera and may inadvertently capture images of people in locations where they might have a reasonable expectation of privacy. Moreover, if a commercial drone crashes and causes personal injury or property damage, the company could be liable for damages under a negligence cause of action.

Implementing a Drone Policy

The full range of regulations and legal risks associated with drone use goes beyond the scope of this article. However, the key point for human resources professionals to recognize is that the law treats drones qualitatively differently than other devices in the workplace. A drone may be smaller than the office coffee-maker – and simpler to use – but it is a commercial aircraft and capable of flying over the property of thousands of people in a single flight. Consequently, employers should closely monitor employees’ use of drones on the company’s behalf.

If the company will rely on regular drone use, the company should consider implementing a written drone policy. Although a company can never entirely eliminate the possibility that an employee will make a mistake when operating a drone, a well thought-out and enforced policy along with training can at least decrease this possibility.

In addition, the company can make itself a less appealing target for enforcement actions by regulators if it can demonstrate that it has policies intended to comply with legal requirements. A detailed policy may also reduce the risk of negligence and other legal claims by bolstering the company’s arguments that any damage was caused by a one-off mistake rather than a systemic failure on the part of the company.

Employers should consider including at least the following five points in a drone policy:

1. Qualifications for the drone pilot

First and foremost, the policy should make clear that no employee may fly drones for the company without approval and without meeting all the requirements of the policy. Employees should understand that any drone operation on behalf of the company could create legal risks for the company. Furthermore, the policy should state that failure to comply could lead to discipline up to and including termination.

The policy also should require the drone pilot/employee meet all the requirements of the FAA regulations. He or she should be vetted by the Transportation Security Administration and certified as a remote pilot certificated with a small unmanned aerial system rating. The policy should establish a retention schedule for documentation of this vetting and certification.

To reduce the risk that an employee’s mental or physical state will interfere with safe operation of the drone, employees should be prohibited from flying drones if they experience a condition that could impair their performance. In addition, employers should avoid creating a working environment in which employees feel pressure to fly drones when they are ill or otherwise impaired. Subject to state mandatory drug testing laws and prior notice and disclosure, companies also should consider conducting drug testing on drone pilot/employees.

If the company will use a visual observer, in addition to a drone pilot, to operate the drone, the company should apply the policies regarding mental and physical fitness to the visual observer too. A visual observer is another individual who assists the drone pilot in flying the drone safely. For example, the visual observer might scan the vicinity for other flying objects while the drone pilot focuses on manipulating the drone. Although the visual observer need not obtain the remote pilot certificate or undergo vetting, the FAA regulations impose the same mental and physical fitness requirements on the visual observer as on the drone pilot.

2. Reimbursement

In many cases, especially at the inception of a drone program, the drones used by the company may be employees’ personal drones. As a result, the drone program should establish a reimbursement process for the costs incurred by the employee in using a personal drone on the company’s behalf. These costs could include wear and tear, loss of the drone, batteries, and repairs.

Some jurisdictions, including California, the District of Columbia, and New Hampshire – require reimbursement for such business expenses. In states that do not explicitly require reimbursement, failure to reimburse employees could damage employee morale and lead to claims against the company, especially if a drone is lost or damaged.

An issue related to reimbursement is off-hours work. Learning to use a drone to accomplish the employer’s purposes may take some practice. For example, it can be challenging to figure out the right angle to take useful photographs with a drone. A court could potentially find that this practice time is compensable work time. Consequently, the employer could find itself at risk of wage-and-hour claims if the company does not have a policy of paying hourly employees for job-related training.

3. Drone operational constraints

Not only the FAA regulations, but also state law imposes detailed restrictions on when and where a drone may fly. The company’s policy should explicitly describe these constraints to avoid any confusion among employees. For example, the policy should describe the dimensions of Class G airspace, which is the airspace in which the FAA permits drones to fly. If the company receives a waiver from the FAA from any of its operational constraints, the policy should explain the precise extent of that waiver. In states that ban drones from flying in the vicinity of critical infrastructure facilities, the policy should state what nearby features likely qualify as critical infrastructure facilities and their location.

4. Drone specifications

The employer’s drone policy should set minimum standards for the drones themselves. These standards should meet not only the FAA’s requirements but also reduce the risk that the drone will malfunction and damage people or property. For example, to meet the FAA’s requirements, the drone must weigh less than 55 pounds, be registered with the FAA, and bear the registration number in accordance with FAA regulations.

To reduce the risk that the drone will malfunction, the company should specify what drone models are qualified to participate in the company’s drone program. Any such drone should come from a reputable manufacturer that meets the company’s operating requirements. For example, the company should make sure that the drone can properly maneuver carrying the camera that the company plans to attach to it.

The company also should consider requiring that any drone purchased for the company include sensors to assist the company in complying with legal operational constraints. For example, a drone pilot can more easily keep the drone under the FAA’s 400 foot ceiling if it has an altimeter.

Last but not least, prior to flying, the drone policy should require the drone pilot to run a through pre-flight check.

5. Privacy

The intersection of drone law and privacy law is still very much in flux, and the precise extent to which a drone can operate without violating privacy rights will likely remain a gray area for years. Nevertheless, employers can take steps to significantly reduce privacy risks while operating drones.

First, the employer should clearly state in the drone policy the business purposes for which employees may use drones on the company’s behalf. Clarifying these purposes can go a long way toward discouraging employees from using drones for illegitimate purposes. For example, an employee might think he is serving the company’s interests by using a drone to spy on other employees engaging in misconduct, but this surveillance may achieve nothing more than exposing the company to privacy-related lawsuits.

Second, to reduce the risk of violating state and federal wiretap laws, employers should prohibit the recording of communications using drones without permission. If the employer will not need audio recordings, the employer should consider disabling any drone audio recording equipment.

Third, the company’s drone policy should generally prohibit employees from flying drones over property without the consent of the property owner or lessee. To increase the likelihood that the property holder’s consent holds up in court, the company should consider including a consent procedure in the policy as well as a consent form as an appendix. If the company must fly the drone over property without consent, the policy should require that drones fly at least 50 feet above the ground and 50 feet from any structure or geographical feature.

Fourth, the policy should prohibit capturing footage of individuals without their permission. To reduce the risk of inadvertently recording employees, the company should consider obtaining consent from employees to be recorded by company drones as a condition of employment. At the least, the company should provide ample notice to employees of any such recording to reduce their expectation of privacy. If the drone inadvertently captures footage of individuals without their permission, the policy should require that the footage be promptly and permanently destroyed.

Drones offer compelling benefits to many employers, but also significant risk in large part because of employers’ lack of familiarity with operating aircraft. Most companies outside of the aviation industry have little to no experience with aircraft-related laws and dangers. However, employers can dramatically reduce these risks by implementing a comprehensive drone policy.