In most workplaces today, it has (quite rightly) become the accepted norm that there can be no room for certain types of conflict – that is anything which constitutes bullying, or any conflict which borders on being discriminatory or that resembles harassment.

The problem for HRDs, however, is that outside of these tight parameters, there is parallel acceptance that certain other types of at-work conflict are now regarded as ‘good’ – if not actually desired. After all, how else can innovation or a great new idea be forged without a clash of ideas/styles or ways at looking at the world?

The problem with all this, of course, is that it creates an interesting philosophical conundrum: Is ‘harm/injury’ (to one’s feelings) now OK?

Should HR professionals – schooled as they often are in ‘conflict resolution’ – turn a blind eye to this type of conflict?

Or, should any interactions that cause distress – even if they are temporary – still be the focus of HR’s activities?

Wherever HRDs think they may stand on this, the issue perhaps becomes even more complicated when it comes to employees who are considered to be neurodivergent – that who already experience life differently from others, and who can already feel overwhelmed by work at the best of times.

To neurodivergent people, conflict can be a thing of great mental anguish – and it’s felt particularly strongly by those who are regarded as introverts.

Introverts are your dominant workers

It may surprise people to learn that introverts are by far (56%) the largest group of employees. And yet, according to research, they are often a forgotten cohort when it comes to conflict in the workplace.

“Organizational design already tends to skew to those who are extravert in nature,” says John Hacktson, head of thought leadership at The Myers Briggs Company, speaking to TLNT. “This already puts introverts at a disadvantage, and so when conflict arises, life for introverts can feel even more overwhelming.”

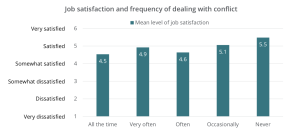

Last year Myers Briggs’ own research found 55% of all workers ‘occasionally’ deal with conflict at work, while a further 21% say they ‘often’ deal with conflict at work; 9% ‘very often’ and 6% deal with it ‘all of the time.’

Significantly, it also found that respondents who had the most conflict also had the greatest job dissatisfaction, while those who had to deal with conflict at work less often had a significantly higher level of job satisfaction:

“What we tend to find,” says Hacktson, “is that introverts’ coping mechanism is to simply try and avoid conflict altogether – or, if that’s not possible, to just retreat and just go along with others for safety’s sake. Ultimately though, this will cause these people to side-step an issue, or withdraw.”

Introverts need to feel supported

He argues the only solution for greater employee happiness, is for HR professionals to try an understand introverts’ default behavioral norm, and then try and encourage a change of behavior that may well go against their natural preference, but which means they will be better equipped at dealing with conflict.

“Introvertedness is really just a preference,” he adds. “And though it may take a while, people can change their initial response behavior to a situation such as conflict.’

He adds: “It’s less about HR saying ‘we must help the poor introvert’, but more encouraging a culture of where everyone is aware of each other’s response types, and how they might have to alter it when dealing with others.”

But does this mean staff have to self-declare as introverts in order for other people to know that they need interacting with differently?

Not so, argues Hacktson: “On the one hand HRDs simply need to encourage people around them to be able to flex their style,” he says. “But they also need to create conditions where people can put their hands up and say that the way they approach things isn’t the same as the way other people approach things.”

He adds: “It’s possible managers will need to learn to accept that people’s preferences for tackling things does differ, and that they shouldn’t try to push everyone into doing things in a certain way if that makes them feel uncomfortable.”

He says: “Things aren’t fixed anymore. In changing times there is only likely to be more conflict, but firms will lose good people because they think differently and are not being accommodated.”

Hacktson in 30 seconds:

Q: Who should accommodates who?

A: Hacktson says: “In an ideal world, extraverts and introverts would accommodate each other, but typically an introvert has to dial-up their behavior first.”

Q: Why should we celebrate differences?

A: Hacktson says: “Differences are good. They are useful because we can end up with a type of conflict which is more useful.”

Q: Isn’t being an introvert a trait that we just can’t change?

A: Hacktson says: “We can change our behaviors, but we won’t be able to change our personality typically. But there’s no reason we can’t change our behaviors slightly.”

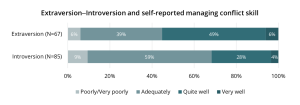

Q: Who thinks they deal better with conflict?

A: Hacktson says: “Perhaps unsurprisingly, a group, extraverts tend to think they deal better with conflict than introverts do.”

Did you Know?

A report by Myers-Briggs found that senior teams expressed higher levels of stress and greater concerns about Covid-19. Managers are more likely to have an extraversion preference than non-managers. Therefore, individuals preferring introversion may deal with more stressed-out extraverted management.

Introverts – The facts:

- Introverts make up more than 50% of the population, but they only account for 2% of senior executives

- Communication styles differ between extroverts and introverts. In a study analyzing the link between extroversion and language, Beukeboom, Tanis, & Vermeulen found that extroverts are more likely to use figurative language and abstractions while introverts focus on facts.

- Extraverts are more confident in their abilities than introverts. Some 87% of extaverts agree that they have the skills to be a good leader, compared to only 56% of introverts.

- Introverts are less likely to express gratitude. Only 67% of introverts express gratitude when they feel it, compared to a significantly larger 89% of extroverts.

- Extraverts respond well to rewards. One theory that explains why this is so is that dopamine responsivity encourages extroverts to reach for rewards, while introverts are more sensitive to punishment.