With ever-rising levels of employee burnout (burnout is officially a World Health Organization-defined ‘occupational phenomenon’), it’s little wonder employees are often described as being in a permanent state of fatigue.

Fatigue is like working while feeling continually drained. Batteries are low and not being re-charged. Fatigue leads to decreased productivity, increased absenteeism and sucks away motivation.

But physical fatigue is only half the problem.

Mental exhaustion is also rife, with recent research by the Society for Human Resource Management finding nearly half (48%) of employed Americans report feeling mentally sapped at the end of each day.

But according to some, it’s one specific form of fatigue that is now spreading across organizations – that of ‘change fatigue’.

Businesses demand constant change – and it’s having a hollowing-out impact

Change fatigue in the workplace is rising.

As companies battle to re-pivot themselves after Covid-19; and as they seek to speed up their own digital transformations (the presence of AI having added additional urgency to this), change is literally all-consuming.

Data now shows that the average employee experienced a whopping 10 planned enterprise changes in 2022, up from two in 2016.

Moreover, according to a report by Gartner, more change is coming, but the workforce is hitting a wall with it.

It finds employees’ willingness to support enterprise change collapsed to just 43% last year. As recently as 2016, this figure was 74%.

The transformation deficit

The Harvard Business Review calls the gap between required change effort and employee change willingness to achieve it as the “transformation deficit,” and according to Jenny Magic co-author of recently published book ‘Change Fatigue: Flip Teams From Burnout to Buy-In’, as HR leaders try to implement systems to improve the workplace during times of uncertainty, change fatigue can make employees resistant to it.

And yet there’s a problem.

If change really is needed, shouldn’t HRDs just plough on through with it?

Can they afford to be derailed from implementing change just because some staff don’t like it?

Or must they be forced into some middle ground?

To help answer some of these questions and others, TLNT decided to sit down with Jenny to hear her views:

Q: What’s the background to ‘change fatigue’? You suggest change fatigue is ramping up – but hasn’t there always been change?

A: “It’s absolutely the case that there has always been resistance from employees to the status quo. However, what we’re finding is that post-pandemic, the sense that change is constant has definitely been amped-up to new levels, and it’s becoming something of a grind for staff. If anything, the pandemic has cemented a new type of active resistance against more change, and staff are now vocally resisting against change, whereas previously they might have moaned about it, but just got on with it.”

Q: What’s driving this particular vocalization against change?

A: “Leadership [or lack of it] is certainly behind a lot of this. But people seem particularly anti-change. Many are running on fumes. A lot of employees really stretched themselves during the pandemic, to ensure that their business stayed viable, and so they’re expecting some sort of reward for this. Yet, instead of this, all they’re getting is demand for even more change. That’s a lot to contend with. Leaders had an opportunity to just to pause for a moment, but this doesn’t seem to have been taken. The problem, is that as leaders press on to prepare for the new business-as-usual, they’re being surprised that they’re being confronted by ‘whining’ people. The issue though, is that lack of trust has been building up; people’s psychological safety has taken a hit, and there is a sense from employees that their bosses aren’t listening to their needs.”

Q: If bosses feel the company needs to push through change, why shouldn’t they? Should they really be held to ransom by change-resistant staff?

A: “I think the ‘because I say so…’ approach no longer works. It’s not a strategy anymore. Companies need to acknowledge and say that change is not fun, and that it can negatively impact the business, but that for change to work, they need to bring people with them. Most change projects don’t work precisely because CHROs don’t think about how people left to deal with it can feel fearful, or stuck. CHRO’s need to better communicate the magnitude of the change. But they then also need to decide what change is worth it. The worst thing is being seen to be pushing change for its own sake, that people don’t actually feel is needed. CHROs need to be having conversations higher up the executive chain, to challenge the board over whether a change project is really necessary. Or, they need to ask if there is a more important change project that ought to be pursued first.”

Q: So, isn’t change just all about managing people’s perception of it?

A: “It’s true that no two staff acknowledge change in quite the same way. However, change in most organizations still tends to follow a parent-child dynamic. The problem is, while leaders may think they are able to command their employees, this is no longer the case. Some might leave – which might be a good thing – but if not managed probably, many will stay but they will breed negativity – which can be corrosive.”

Q: So what should CHROs have in mind?

A: “They absolutely have to address why change is happening in the first place, to make it relevant and understandable to people. They then need to ensure staff realize for themselves the ‘need’ for change. The mistake many leaders are making, is that they are trying to use change as a lever for re-establishing a form of control over staff that they feel they have lost, and this is where change is going wrong.”

Q: Is perhaps the best solution not to call a change project ‘change’ at all?

A: “There’s a school of thought that says as soon as you give something a label, and call it a ‘change project’, then it instantly gets people’s back up, when really it could just be regarded as evolution or adaption, which most people more instinctively buy into. However, sometimes business call things adaption when there are pretend changes. We can’t – and shouldn’t – disguise change for what it really is. The point CHROs need to get to, is that everyone perceives change differently, and that not everyone can change all at once, and so there needs to be a roadmap for different groups about when and how the change is coming, and what it will mean for them.”

Q: Doesn’t this just make change even more complicated, if you have to devise individual roadmaps for everyone. Isn’t this why leaders just try and force it through – to avoid this?

A: “I’m afraid it’s just what’s needed, and change will happen better if this approach is taken. It takes empathy to say to people that change involves loss of some sort. Resistors to change need to be given a safe place where they can talk about it. They need to feel that they will be unpunished for raising concerns about it, because often these same resistors have great insights about why a particular strategy for change may not work. When CHROs involve these resistors, just giving them involvement is often enough to turn these people around, and convert them from having the most vocal opposing views, to being be loudest advocates for change.”

What the research says…

Last year Capterra’s ‘Change Fatigue’ survey revealed:

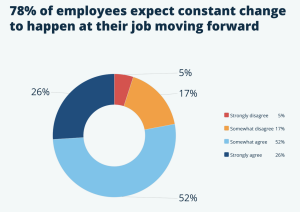

Employees sense change is always happening:

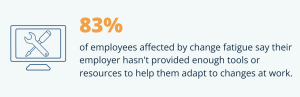

Employees don’t feel supported through change:

Gartner finds:

Most employees find change to be stressful:

Managing change fatigue is HR’s top change management concern for 2023: