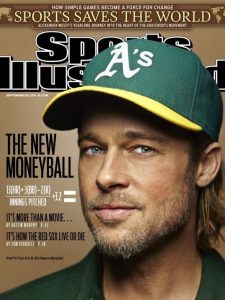

What’s it like to have Brad Pitt play you in a movie? Billy Beane, general manager of Major League Baseball’s Oakland Athletics, is one of the few people in the world who knows how it feels.

The reason Beane is the subject of Moneyball, a (New York Times best-selling) book and (Academy Award-nominated) movie, is because of his revolutionary methods of evaluating baseball players. He used objective, advanced data to make his baseball hires instead of more traditional statistics and gut instincts. It doesn’t sound crazy but it flew in the face of everything that people who evaluated baseball talent thought at the time.

His unique approach to talent management is why he keynoted the inaugural TLNT Transform conference in Austin, Texas, and his unusual approach has lessons for all executives, talent managers, and HR pros.

Thinking differently

Utilizing statistics shouldn’t be revolutionary, especially in a field like baseball that has millions of dollars invested in talent evaluation and player costs. But when faced with modest resources that were dwarfed by most other teams, Beane had to think differently about talent management than his competitors because they would always be able to beat him when it came down to salary and traditional analysis of baseball players.

If you know anything about baseball, you probably have an idea as to what a typical baseball player looks like. You probably know something about strikeouts and home runs. And if you have a trained eye, you probably see other factors like stolen bases and walks. Baseball scouts also considered aspects like height, swing power, arm strength, and so on.

If you know anything about baseball, you probably have an idea as to what a typical baseball player looks like. You probably know something about strikeouts and home runs. And if you have a trained eye, you probably see other factors like stolen bases and walks. Baseball scouts also considered aspects like height, swing power, arm strength, and so on.

Instead of looking at all of those statistics and trying to just guess how much they would impact the games, Beane and his team (including his assistant, Paul DePodesta, played by Jonah Hill in the movie) broke it down into a few factors that would almost always put them in a better position to win. On the offensive side, it was players who avoided outs and got on on base more often. If you don’t get out and can get on base, you were always in a better position to win the game.

And while batting average and home runs can help determine that, directly measuring those factors that help players get on base (and not get out) is the simplest way to determine whether your offense is going to score. Directly measuring those factors led Beane, DePodesta and company to find valuable players outside of the stereotypical (and easily recognized) baseball players.

The error of emotional, gut decisions

Data-driven decisions can be come off as completely heartless, baffle people, and defy explanation, especially to the casual observer. Focusing not just on data, but the right data, means better decisions.

Beane mentioned the fact that he doesn’t watch this team’s games. If you’re devoted to winning on the back of the data of performance, watching an individual game (instead of considering the statistical body of work over many games) can lead to bad (and emotional) decision making.

Beane mentioned the fact that he doesn’t watch this team’s games. If you’re devoted to winning on the back of the data of performance, watching an individual game (instead of considering the statistical body of work over many games) can lead to bad (and emotional) decision making.

Making smart decisions is critical in business as well, yet so often, HR and recruiters take the lure of faddish interview techniques that are based on bunked or non-existent science. You might luck out but wouldn’t it be better to put yourself in the best position? Evaluating people based on how they can help your company perform better and trying to take the emotion and those considerations that don’t matter out of the decision making process. As Beane iterated several times, there isn’t any business that can’t benefit from focusing on what is very truly the root of their success.

Success trumps culture?

During the question and answer portion, an attendee asked about whether Beane would bring on a baseball player who had the talent but might be a bad cultural fit. Beane suggested that in his experience, success and winning fixes culture — and that great culture (without the talent) doesn’t win. Outside of a truly destructive cultural force (that can often derail a team’s performance on the field), being successful and having talented individuals on your team can drive better culture.

While not taking anything away from the point, this is always posited as an either/or proposition. In how many real-world situations is the person who is the worst cultural fit also the most qualified based on objective measures? More frequently, people are arbitrarily eliminated because they aren’t the best cultural fit, even if they have the talent and tools to otherwise be successful.

A sensible Moneyball approach in business doesn’t demand that you completely disregard culture; it simply demands that you consider objective talent and performance measurements first and that you consider candidates who may not fit traditional stereotypes of success and culture in your industry. That lesson, nearly 10 years after the publication of the Michael Lewis book, still resonates powerfully for those who consider talent management critical to business success.