With the potential for whistle-blowing employees to reap hundreds of thousands, even millions, in bounties for reporting securities violations, companies are understandably concerned that they may become the target of a claim.

Worry, though, isn’t translating into planning for what to do about the tipster.

A survey by Littler Mendelson, one of the nation’s largest employment law firms, says only 54 percent of the mostly S&P 500 firms responding are confident managers and supervisors know not to retaliate against whistle-blowing employees.

When you consider that 45 percent of companies have already had claims filed against them, and two-thirds expect claims to increase in the near future, it’s remarkable that 32 percent of the respondents admitted they lacked confidence their leaders knew how to treat tipsters. The balance, said they just didn’t know if their managers and supervisors “understand unlawful retaliation concepts and know not to engage in such conduct.”

When you consider that 45 percent of companies have already had claims filed against them, and two-thirds expect claims to increase in the near future, it’s remarkable that 32 percent of the respondents admitted they lacked confidence their leaders knew how to treat tipsters. The balance, said they just didn’t know if their managers and supervisors “understand unlawful retaliation concepts and know not to engage in such conduct.”

HR needs to be involved with whistleblowers

When almost half the S&P 500 companies doubt their training, what does that mean for other publicly held (and privately held companies with SEC reporting obligations)?

Warns Edward T. Ellis, co-chair of Littler’s Whistleblower and Retaliation Practice Group, “It is critical that executives and managers be trained on compliance with laws that affect their businesses as well as best practices for handling whistleblower claims when they arise.”

Created by the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, the whistle-blower program rewards tipsters with as much as 30 percent of court awards and settlements in actions filed by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The final rules setting the program in motion took effect in August. Already 191 cases have been filed that might result in a whistleblower windfall.

While investigating claims made by whistleblowers is not the role of Human Resources, ensuring the whistle-blowing employee isn’t retaliated against is. It’s here that HR needs to act to avoid the possibility of a suit by an aggrieved whistleblower.

In a post on Business Management Daily, Russell E. Adler, an attorney with the Labor and Employment Practice Group of Pepper Hamilton walks through a hypothetical situation, offering step-by-step instructions on how to handle a reporting employee. Step one: Treat the matter seriously from the start. “There is substantial risk in hastily dismissing the complaint as without merit, absent strong supporting evidence,” Adler writes.

In a post on Business Management Daily, Russell E. Adler, an attorney with the Labor and Employment Practice Group of Pepper Hamilton walks through a hypothetical situation, offering step-by-step instructions on how to handle a reporting employee. Step one: Treat the matter seriously from the start. “There is substantial risk in hastily dismissing the complaint as without merit, absent strong supporting evidence,” Adler writes.

According to the Littler Mendelson survey 84 percent of the survey respondents have already taken some preventive steps to protect themselves against retaliation claims, which means 16 percent haven’t.

Updating compliance is crucial

Even if you’re not in the 16 percent, are you confident that the steps taken up to now are adequate? Many companies implemented compliance and enforcement programs when Sarbanes-Oxley was adopted in 2002. Now, with Dodd-Frank in place and the SEC’s Office of the Whistleblower open and doing business, Little Mendelson says updating compliance is crucial.

“Many companies have strengthened their internal compliance procedures since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was enacted in 2002; however, these programs may not be effective under Dodd-Frank,” says Gregory Keating, co-chair of Littler’s Whistleblower and Retaliation Practice Group. “This regulatory shift creates a need for companies to modify their programs to be better prepared for new regulations and increased whistleblower exposure.”

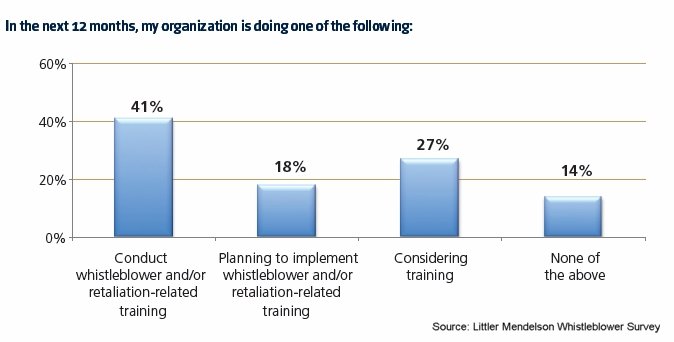

What should be worrisome for HR is that of the S&P 500 companies in the survey, only 41 percent have concrete plans for whistleblower training in the next 12 months, while 18 percent plan to implement training. The rest are either thinking about it or have no plans.

One last caution about the potential for exposure. The government’s chief of the whistleblower program made clear in a speech the day before the rules went into effect in August that even marginal tips — “gut feelings,” he called them — can be enough to trigger retaliation protections and earn a reward.

A gut feeling may not be enough to open an SEC investigation, said Sean X. McKessy, chief of the whistleblower office:

If, however, the employee were to report that gut feeling internally, and the company’s subsequent investigation were to uncover specific, timely and credible information that is reported to us, the reporting employee –- who might not have otherwise even qualified for an award –- would then be eligible.”