As an employment lawyer and frequent speaker on employment law and human resources issues (approximately 200 engagements annually), the topic I’m increasingly asked to talk about is implicit bias.

Thankfully, HRDs and senior leaders across the country are recognizing that not only do they have a responsibility to identify the existence of implicit bias, but that awareness of the problem on its own is not enough.

For want of a better phrase, most people really do seem to want to do better and be better. They want to minimize the impact such bias has on their decision-making processes.

They want to move beyond simply understanding it and towards implementing solutions for mitigating against its infection.

Most people?

There still remains, however, a sizeable group of individuals who seem skeptical, if not cynical, about both the existence and impact of implicit bias.

This group contends they have no implicit bias and, accordingly, their decision-making cannot possibly be influenced by the notion.

Whether it’s through meeting these people in educational sessions, or just meeting them in their own world of work, these people’s refusal to try and comprehend implicit bias normally starts with something along the lines of them saying: “Well, back in my day…”

Hmm…

My wife, Jamie, and I recently saw the movie A Man Called Otto.

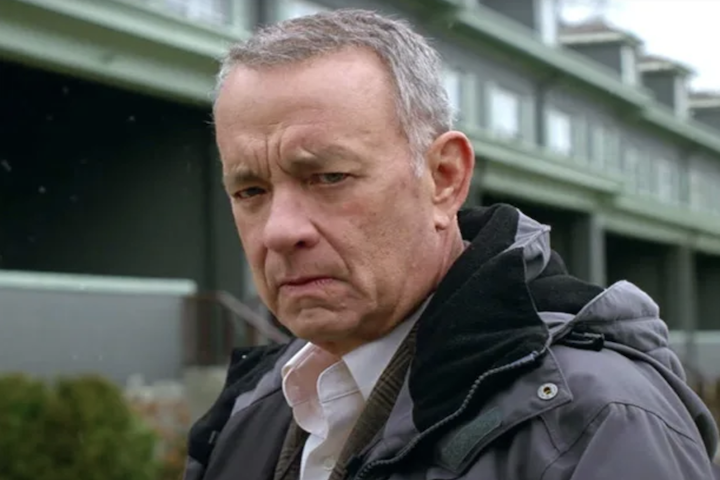

The main character, Otto Anderson, brilliantly portrayed by Tom Hanks, is the embodiment of the “back in my day” way of looking at the world.

He is mired in a time gone by and presents a steadfast refusal to recognize some of the realities of the time in which he is living.

While some of his reasons for holding on to the past are tragically beautiful, he views the world through a lens replete with implicit bias. But, unlike many decision-makers inside of organizations, during the course of the movie (and most notably through his relationship with a transgender former student of his late wife), Otto comes to recognize the existence of his bias and moves forward far less impacted by these anachronistic notions of reality.

What can we learn from this?

Is Otto free from implicit bias entirely?

No.

Implicit bias never completely disappears. But, Otto’s recognition of its existence and his attendant desire to take meaningful steps toward mitigation of its effects serves as a playbook for decision-makers in all organizations.

Here’s why. Implicit biases, or unconscious biases, underlie the attitudes and stereotypes that people may unconsciously attribute to another thing, person or group that may impact how they understand and engage with a person or group.

These biases, which serve as the contextual lens through which we view the world and the people in it, are informed by myriad of factors and, if left unchecked, truly can affect and infect your organizational decision-making at all points and in all processes.

Implicit bias manifests itself in many forms, including affinity bias, confirmation bias, race, age, gender or even name bias, just to list a few.

So, what can we do to prevent these biases from impacting our actions?

Step One: Recognize its existence

It is impossible to try to mitigate the effects of implicit bias unless we recognize its existence. Stated simply, we all have implicit bias.

They are not necessarily of our conscious or even stated beliefs. Typically they are based on an emotional or visceral (rather than rational) response.

Given the multitude of variances in our backgrounds, to refuse to acknowledge the existence of implicit bias would be to say that our experiences have no bearing on who we are and what we do. Not possible.

Step Two: Understand the sources

Implicit biases derive from many sources. Some of these include where, when and how we were raised; who our friends and family are; where, when and how we were educated; who our colleagues are; what kind of media we consume, etc.

All of these influence the contextual lens through which we view the world and, in turn, enable us to sift through and distill innumerable sensory cues to conduct a threat analysis of a person, situation or event that then informs our next steps.

Unless we realize that these sources have such a meaningful impact on our actions, we will never successfully be able to prevent our biases from influencing our actions.

Step Three: Take steps to minimize effects

Understanding both the existence and the sources of implicit bias are critical steps. But now we have to mitigate against such bias interfering with decisions designed to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion.

To do this, we must continue to consume content and to become educated on biases and confront them when they appear. Remember, this is a journey and there is no end point when we can stop and assume such biases cease to influence our thinking.

Second, do not attribute the failure of one person to an entire group. For example, if a mother of young children does not handle adequately an assignment, do not assume that women with young children, as a whole, cannot effectively handle similar work.

Third, when you stumble, recover. We all are human and make mistakes. When you make one, apologize for its effect and move forward, paying close attention not to commit a similar infraction.

Fourth, colorblindness is never a solution. Saying “I don’t see color” is not only disingenuous, but it is wildly insulting and sends the message that you do not see the totality of the individual before you. If you are sighted, you see color. You see gender or gender identity or expression. So be authentic.

Finally, before you make any decision, ask yourself whether your bias is influencing you. If so, recalibrate and ensure such bias does not infiltrate subsequent decision-making.

Remember this: Otto Anderson personified the ability to change. He understood, through time, that adhering to anachronistic and overly simplified notions about who people are rendered him a relic. who was unable to adapt to a more modern and constantly changing world in which he actually lived.

And it was in this recognition that his view of people and events became less influenced by his bias and more open to acceptance of things that he may not completely understand.

For Otto, it was the memory of his beloved late wife and her relationship with a transgender student that provided this impetus for adaptation and his letting go of “back in my day.”

Where will your journey begin?