When Fiat Chrysler chief executive Sergio Marchionne recently passed away, the corporate world mourned one of the greatest turnaround leaders of the modern business era. Marchionne was one of the auto industry’s most tenacious and respected CEOs, who took over Fiat in 2004 and spearheaded the acquisition of Chrysler in 2009.

At the time, both businesses were near bankruptcy and most gave him little chance of success.

But he proved his naysayers wrong, and through 14 years of aggressive deal-making and an uncompromising focus on results, he multiplied Fiat’s value 11 times over, pulled both brands from the brink of bankruptcy and grew the company to become the seventh-largest automobile manufacturer in the world.

A common problem

Marchionne was known to be a chain-smoking workaholic, working 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year. So, when he died at 66 years of age, leaving a partner and two sons behind, some asked the question: was it worth it?

This question is not uncommon in corporate circles, with many executives around the world putting in demanding hours to deliver on the expectations required in their roles. This lack of balance is taking a significant toll on both the physical and mental health of executives.

While few executives publicly acknowledge burnout, researchers studying the issue say it is more prevalent than previously thought. According to a 2013 study of senior managers and C-suite executives, about half thought the CEO of their organization was burned out while 75% said their senior managers were burned out. The study, which was conducted by Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Srini Pillay through consulting firm NeuroBusiness Group, found that the three top causes of burnout were work overload (69% said they were functioning at their maximum capacity), powerlessness and insufficient reward.

Burnout at all levels also have a cascading effect on businesses, their culture and talent management, according to a national survey of 614 HR leaders conducted by Kronos. It found that 95% of them admit employee burnout is sabotaging workforce retention, and two of the main contributors to burnout include unreasonable workloads (32%), and too much overtime/after-hours work (32%).

“The impacts inside and outside of work are many,” says Paula Davis-Laack, a global expert who helps executives prevent burnout and build stress resilience. Having worked with organizations including Coca-Cola, GE Healthcare and Harvard Law School, she has seen first-hand the impact burnout can have an both individuals and organizations.

“At work, there is decreased wellbeing, lower staff retention, higher organizational system costs, higher turnover rates, lower morale and lack of cohesion in the organization as a whole.”

Burnout goes to the heart of personal health and wellbeing, and Davis-Laack says burnout is related to an increased prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders, alcohol dependence, higher levels of sleep disturbance, headaches and stomach/GI infections. It is also an independent risk factor for infections like colds and for type 2 diabetes. Research has also found that burnout and absenteeism are related, with the exhaustion component of burnout correlating with long-term sickness (90 days or more).

Recognizing burnout

The NeuroBusiness Group study focused mostly on male CEOs, with each of them describing wanting to “power through” their stress. A Wall Street Journal report on the study quoted one CEO saying, “If you want to be a real leader, you can’t go around being emotionally erratic.”

Another CEO said he felt like he was “running in place” but hesitated to call his condition “burnout.” Denial is a major problem in recognizing pre-burnout symptoms; a Harvard Business School professor explained that many executives don’t have “good thermostats” for figuring out when they’re reaching the edge.

“As human beings we normalize our world and think that operating in high-intensity mode is just what we do. But this is like a frog in boiling water, and before you know it this stress becomes the new norm – and that is the dangerous part,” explains Stuart Taylor, CEO of Springfox, a consulting firm which helps organizations, their executives and employees build resilience and combat burnout.

“A lot of us think that we need to be up there in organizations, working hard to we can meet external priorities. But you need to look after yourself as well, otherwise you won’t be healthy enough to look after those priorities.”

It is important for executives, their friends and particularly HR to recognize the indicators of burnout – otherwise known as a “brownout”, according to Bella Zanesco, CEO of wellbeing strategy consulting firm Wellboard. She says burnout is a seven-stage process – the first three of which are indicators of a brownout:

- Frustration (For example: “I can’t do this” and “It’s too hard.”)

- Anger (“I won’t do this” and “It’s your fault” – lashing out)

- Apathy (“I don’t care”)

- Burnout (collapse/crash/adrenal failures)

- Withdrawal (either presenteeism or absenteeism or withdrawal from life or workplace)

- Self-knowledge/acceptance

- Recovery

Importantly, Zanesco says the process of recovery can often take twice as long as the first six steps.

What HR can do

Burnout is both an organizational and individual issue, according to Davis-Laack, who says companies and their HR departments really need to focus on the balance of job demands and job resources. Job demands are those aspects of a person’s work that take consistent effort and energy, while job resources are those aspects of a person’s work that are meaningful and energy-giving.

She explains that HR is best served by first focusing on increasing job resources, particularly in the areas of autonomy, belongingness (development of high-quality relationships), mastery (helping employees get better at more and more challenging tasks so they don’t stagnate), giving consistent feedback, and consistent recognition.

HR can also help to mitigate job demands, and she says it is particularly important to minimize role ambiguity (“I’m confused about what I should do or don’t have enough info to properly carry out the task at hand”), role conflict (lots of assignments coming from multiple sources: “I don’t know the priorities”), as well as unfairness.

Zanesco explains that burnout is often a self-perpetuating issue within organizations, and it’s up to HR to identify this within the cultural nuances of the organization. “Many young leaders are quite balanced when they join, but they are entering an ecosystem which is unbalanced. So, they have to abide by the cultural practices of the organization, working late, burning the candle at both ends and being available 24/7. So, the problem is 50/50 between organizations and individuals,” she says.

She says HR should also watch for certain personality types which are more prone to burnout: these include insecure overachievers, perfectionists and type As.

Executives must become self-aware

For individual executives, Taylor said the process really starts with attending to their own needs, so they can participate in life more fully. “This starts with raising awareness around the journey they can take, and this provides them with an ability to take steps to bounce back,” he says.

“There are steps in the journey to burnout which executives need to understand, from stress, emotional withdrawal, mental fatigue and ultimately spiritual failure – which is also called depression. They need to have the self-awareness to know when they are not traveling so well.”

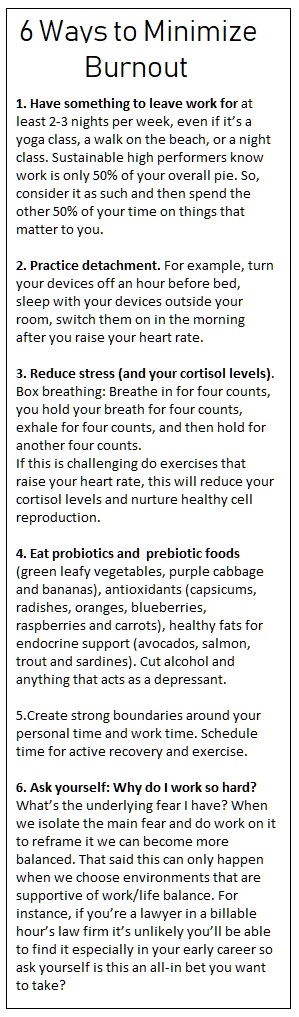

Executives also need to make sure they are well connected on a personal level, so others might be able to pick up on precursors to burnout. They also should actively engage in wellbeing strategies around sleep, exercise, nutrition and meditation. “Play hard and rejuvenate hard,” Taylor recommends.

Organizations and HR should also focus on building cultures of trust, particularly at executive levels. “The alternative is a fear-based culture, which is one of the pathways to stress and ultimately burnout,” he says. “Remove the stigma around mental health in the workplace, and this is achieved through awareness and education.

“Wellbeing strategies need to be encouraged at organizational level, so executives set the example for others in taking the time to look after themselves.”