Last week TLNT reported on the rise of a worrying new trend that HR professionals now have to contend with: the emergence of the ‘career downsizer’.

‘Career downsizers’ are people who voluntarily choose not to take the next step up in their career (or decide to take a step down from their current role).

Although these moves can be defined as voluntary decisions, what’s significant is the fact these people are not necessarily doing it because they feel like they have any choice.

Instead they’re doing it because they feel stressed and burned out, and are taking a step back in the interests of their own wellbeing, and because – let’s face it – they see HR as having failed them.

In speaking to Jasmine Escalera, career expert at MyPerfectResume, the consensus was that if rising numbers are put off from making their next career move (because of the extra wellbeing implications it has), this could have serious implications for organizational structures.

But could another, parallel, trend potentially come to HR professionals’ rescue?

Some say there could be – because commentators are also beginning to remark about a different trend – ‘unbossing’.

The rise of ‘unbossing’

Recently discussed in Forbes ‘unbossing’ is being described as the practice of companies shedding scores of mid-level and middle management roles, in the desire to be more lean and efficient, and reduce bureaucracy and decision making.

The theory, is that as traditional intermediary-level bosses are removed, it creates a much more direct line of communication between employees and senior executives.

Forbes describes it as resulting in a flatter organizational structure, giving staff clearer visibility to senior leadership – which in doing so potentially mitigates “the inefficiencies associated with excessive layers of command.”

While some claim this could have serious downsides – not least because middle managers often serve as vital conduits between frontline employees and leaders; providing guidance and support – the fact middle levels are being axed just as staff are deciding they don’t want the stress of moving into these role anyway could be seen as bit of a result.

These middle manager roles seem to be going just as career downsizers are questioning whether they want them anyway.

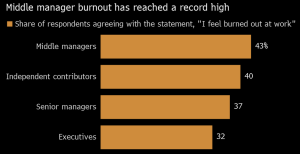

After all a recent survey by Slack Technologies Inc.’s Future Forum found those in middle management are the most exhausted of all organizational levels. Some 43% said they’re burned out.

Source: Bloomberg

So should CHROs be actively pursuing ‘unbossing’, or is there something about this trend that they should be trying to quell and push back against?

The trouble with unbossing

“On the one hand, ‘unbossing’ is a very drastic measure,” argues David Satterwhite, CEO of Chronus – speaking exclusively to TLNT.

“What it’s saying is that instead of trying to make mid-level workers more efficient or better at their jobs, it’s a policy all about getting rid of them completely,” he observes.

“The trouble with this,” he continues, “is that it’s a policy that actually deviates from what the real problem of organizations is – which is how to make managers ore effective.”

He adds: “The issue in organizations is disengagement; and its managers that are vital for having conversations with staff and listening to them. Mid-level people are vital.”

Reversing disengagement

Data consistently suggests that what drives engagement is people’s relationship with their direct manager – with Gallup finding that 70% of the variance in team engagement alone is down to the manager they have.

As such, Satterwhite says unbossing is the very worst thing companies can be doing right now.

“Instead of creating better leadership, it’s just getting rid of people. Instead, what companies really need is better ways for employees to ‘connect’ with their managers,” he says.

He adds: “The error companies often make, is that they get caught up with making efficiencies and change rather than getting employees on the side of change.”

Rather than reducing mid-level headcount, he argues CHROs need to instead concentrate on what he calls “reversing the things that lead to disengagement.”

“I think companies need middle managers,” he says. “I think companies need people who are in touch with how people are feeling and how they are doing. Management of people needs to be something that’s intentional, not something that can be stripped away when someone thinks it’s no longer necessary.”

He adds: “Most people come into leadership through an operational route. If people feel stressed and burned out by moving up into these roles it’s because they need to be taught how to be a manager.”

He continues: “Generally speaking, I find that most employees don’t actually mind being micro-managed – but only if it’s a style of management that helps them be more successful.

“It’s when staff are no better off with managers being there that managers are not effective. But I return to my first point – if that’s the case, the answer is not to get rid of managers, but to make them more effective.”

What does the future hold for middle managers?

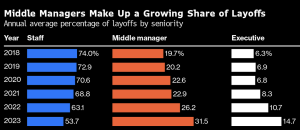

Source: Bloomberg

Last year, Fortune pre-empted the unbossing trend by writing that middle managers are “the prime layoff target”, after Meta announced that 2023 would be its ‘year of efficiency’ – laying off 11,000 staff – or around 13% of its workforce.

Numerous companies have since followed – including Google, and Intel, and several more this year.

Of course, what we do know, is that the shedding of middle management is not actually new.

It’s been going on for decades. A study of 300 large companies found the number of managers layered between CEOs and their division heads decreased by more than 25% from 1986 to 1998.

However, commentators do seem to agree that cuts to this important level should only go so deep.

Last year Business Insider decided it wanted to ‘Save the Middle Manager’ – arguing over-flattening of organizations threatened productivity and performance, by not having vital supervisory function.

So what does Satterwhite say?

“If recent history tells us anything, it’s that we tend to ebb and flow around perceptions of middle management.”

He says: “Right now the pendulum does seem to be moving to having fewer middle management, but I personally feel there is a huge place for this cohort of people.”

He adds: “The key is developing managers, so that they can manage effectively, and prove their worth. When companies start thinning out management, what they’re really saying is ‘how many managers can I get away with removing?’ This is not really a conversation I like.

“Instead,” he concludes, “we need to be asking what development we can be giving to our managers. CHROs must invest more in the training of their managers. Sometimes the amount of management we need can be a chicken and egg question, but I say the more we invest in making managers better, the better that will be for organizations.”