This post is a salute to passionate and experienced culture and performance change agents. You understand the power of culture in organizations and the challenge, frustration, restlessness, and exhilaration inevitably linked to intentional culture-related action. We’re living in the absolute best time in history to be involved in meaningful culture change. Culture is finally a topic of discussion in most organizations, and we need to make the most of it.

During an early-morning run by the Washington Monument early this summer, I saw the flags at half-staff due to the Santa Fe High School shooting in Texas and started thinking about the incredibly challenging culture-related issues in organizations and society as a whole. I thought: It’s going to take every bit of experience and knowledge to tackle these issues, and a general how-to guide barely touches the surface of what we need. I shifted my focus to zero in on details often missed in culture-related change efforts, even by experienced change agents.

Unless you are some sort of crazy unicorn, we all can benefit from learning from others, especially with something as challenging as shifting or evolving culture. We spend so much time trying to understand the stories and examples from great cultures or listening to the latest inspiring keynote, but we rarely dive into the messy culture realities and specific approaches to change. These seven insights will, hopefully, add to your experience in some new and impactful ways.

1. Unite the organization to support the purpose and top priorities

I recently had a conversation with a manager who said leaders at her organization think of culture as being “soft.” This absolutely broke my heart, but it’s the reality in many organizations. It doesn’t matter if the current culture is crippling the organization and costing billions or keeping the organization from living up to its fullest potential.

My culture reality is different. I didn’t gain a passion for the subject of culture from being an educator or consultant. I started learning about culture around the same time I was promoted to fill a senior leadership role with full P&L responsibility. I was excited about the opportunity, but also plagued by a feeling of panic inside as I listened to the critical, self-doubting voice in my head. I was fortunate that the very experienced VP of Operations I partnered with in multiple roles had the attitude of “every team member feeling like they were part of a group running their own business.” It didn’t matter if it was a department, plant, warehouse, or cross-functional group. This resonated with me. The knowledge of the business, ownership, teamwork, and expectations for proactive action would be so strong it would propel our organization forward.

We worked together with the rest of our leadership team to define an “involvement culture” that was all about uniting our organization in support of our vision and most critical performance priorities. There was an incredible sense of urgency each year as we connected our “involvement culture” habits and systems to one or more specific business priorities like quality, safety, growth, customer experience, and innovation.

This concept of “uniting the organization” behind a critical improvement priority has resonated repeatedly as I engage with other leaders. The frustrations, inconsistencies, and challenges top leaders experience when managing their most critical performance improvement priorities often connect back to culture in some form.

I love seeing the light go on when a top leader begins to understand the idea of culture-related understanding and change being the key to uniting his or her organization to support the top improvement or performance priorities. This builds naturally out of a discussion regarding the most critical priorities they are managing and the frustrations or challenges they have “bringing their team together” to deliver the results they are targeting. Remember to think about what mission priority you are attaching a culture engine to, and avoid generic culture plans with no clear connection to outcomes or results. Culture is the fuel to maximize the potential of an organization, and it’s definitely not “soft.”

2. Connect culture transformation to the personal drive of the top leader

I have never encountered a culture that couldn’t be changed, but I have met plenty of leaders who are culturally blind to the problems they need to solve. I always love interviewing the senior management of an organization, especially the top leader. One discussion can provide tremendous insight into what drives them and whether that deep personal drive can be connected to culture-related change. I used to think you could build this relationship over the course of an improvement effort. I was wrong; that’s too late. The entire tone of the work changes after a gut-level connection and understanding is achieved. Resist the temptation to be an expert, especially in initial interactions. Everything you say and do can influence the change effort. There needs to be less judging, less talking, and more questions.

I learned to use the following question at the end of interviews to build trust and make a stronger connection with the personal drive of the top leader: “We have discussed the reasons and targeted outcomes for this work, but that’s been focused more on the overall organization. Why is it important to you personally that we successfully evolve the culture in meaningful and impactful ways?” Some respond with more “business reasons,” but most open up and tell a story that connects the work to something far more personal in their background.

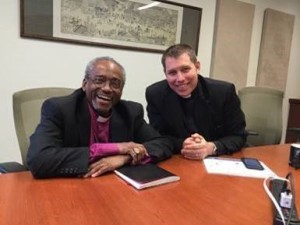

The most interesting response I received came from Presiding Bishop Michael Curry of the Episcopal Church. You may know that name. He delivered the message at the recent royal wedding. We had a great discussion that ended with the “personal” question. He sat back and thought for a good 10 to 15 seconds. My mind was racing as he said, “I grew up in a family where there was an expectation that what you did with your work was going to change the world.” He also shared, “We’ll know it’s working and having the impact we need when random people know our work and hear the version that is not judgmental or hypocritical.”

This was what we needed. We talked about how the “expectation” word is powerful when it comes to culture and the cultural norms or “unwritten rules” that people are bombarded within organizations. That expectation he felt growing up was a splendid example of a constructive and encouraging expectation reinforced in countless ways. I could have preached to him about culture for hours, but it would have been meaningless without a more personal understanding. I would have missed this deeper connection if I didn’t ask that final question.

Larry Senn, founder and chairman of Senn Delaney, defined a great analogy for the process to help leaders understand the impact of culture: “You need to manufacture an Aha.” I love this concept because no “aha” means no culture change.

3. Stop using the word ‘culture’ so much

I was discussing a couple of very challenging improvement efforts with Edgar Schein. I am freakishly driven when it comes to culture, but not free from fear, so I was a little intimidated sharing plans with a top culture pioneer. He was very encouraging, and then he stopped me: “Tim, you’re not going to like this, but you have to stop using the word ‘culture’ so much. People don’t know what you are talking about.” He emphasized the need to understand if I was talking about a value, behavior, norm, or something else. I think many of us get sucked into this trap of using the “generic culture word.” It undermines our work.

I was discussing a couple of very challenging improvement efforts with Edgar Schein. I am freakishly driven when it comes to culture, but not free from fear, so I was a little intimidated sharing plans with a top culture pioneer. He was very encouraging, and then he stopped me: “Tim, you’re not going to like this, but you have to stop using the word ‘culture’ so much. People don’t know what you are talking about.” He emphasized the need to understand if I was talking about a value, behavior, norm, or something else. I think many of us get sucked into this trap of using the “generic culture word.” It undermines our work.

It’s far clearer for everyone involved to avoid referencing culture and culture change by using language like:

- Solving problems or accomplishing goals.

- Overcoming significant frustrations with collaboration or teamwork.

- Understanding patterns of behavior, norms, or “unwritten rules” negatively impacting results and why they are so deeply entrenched.

- Resolving inconsistencies with behaviors that are undermining results.

- Reducing fear and hesitation that are holding the organization back.

- Involving, empowering, and encouraging proactive action.

- Driving shared learning and results as a team.

These areas can be probed without ever mentioning the word “culture.” Culture can then be introduced in the context of their stories, examples, and language instead of your language.

4. Understand the current climate and underlying culture

Robert Cooke, CEO of Human Synergistics and author of the Organizational Culture Inventory (OCI), said: “One of the problems we have with culture is that everything has become culture.” Much of what people are referring to when they think they are talking about culture is actually organizational climate – the shared perceptions and attitudes of members of the organization.

I was facilitating some focus groups recently with a major university partner and corporate client. Nearly every individual in the focus groups felt compelled to jump in and start talking about examples of screwed-up systems, structures, or leadership approaches that were all aspects of the work climate. It was messy work pulling them back to help them understand patterns of behavior and why they were so deeply entrenched. We’re not used to talking about the invisible realm of culture: values, beliefs, assumptions, and norms. This inability to go deeper is crippling organizations as we deal with surface changes to the work climate that may have little or no impact on the underlying culture. We layer on more systems changes, training, or some “new program” defined with little or no understanding of the “real” culture.

Most people in organizations are not trying to frustrate each other and intentionally undermine success through behavior that is less than ideal. There are logical reasons why behavior interpreted as being frustrating, rude, or insensitive persists. We need to understand “patterns” of inconsistent or undesirable behavior and the shared beliefs or assumptions driving them. What is driving that “fear of speaking up” or the “just go along with things” mindset? Why aren’t leaders involving team members in major decisions that impact them?

Most “culture experts” focus on “culture alignment” or behavior change but, as Edgar Schein warned, “Don’t be seduced into thinking that behavior change is culture change.” If cultural attributes (e.g., norms, values, beliefs, etc.) aren’t evolving, the success of a change effort may be short-lived. The frame to understand culture must go beyond the work climate and observable behavior. It’s not sufficient, it distorts things and a deeper understanding is possible with additional effort.

5. Follow a qualitative-quantitative-qualitative assessment sequence to understand the current state of the culture and climate

I am an enthusiastic fan of “real” culture surveys (the rare ones that measure values and norms), but I think it’s short-sighted to jump to a survey as an initial step in a change effort. It’s incredibly important to start by understanding why there is an interest in culture. What problem are you trying to solve? What goal are you trying to achieve? It helps to understand the current perceptions about culture and climate and how they are both helping and hindering progress with specific improvement goals or priorities. It often helps if the initial qualitative effort is not biased by already having feedback from a survey. It’s easier to stay in an inquiry mode if you don’t already have some of the “answers” from a survey. The initial qualitative step may also help with identifying custom items to add to a standardized culture and climate assessment. The survey can then be used to develop a baseline language and measurement regarding some aspects of the current culture and climate.

Culture survey

The survey, or quantitative, step will reveal characteristics of the work climate and culture that were not mentioned in the initial qualitative step. This should not be a surprise, because culture is like the water we swim in or the air we breathe. Most “experts” jump to action planning or defining improvement efforts right after combining qualitative and quantitative methods. This is a missed opportunity because it can be incredibly beneficial to return to a second round of qualitative assessment to understand 1) why characteristics from the quantitative assessment were not previously mentioned, and 2) how these characteristics are influencing the aspects of the culture and climate that were identified.

I was facilitating some focus groups with a consulting partner at a manufacturing client who was interested in reliability improvement. One focus group was held with middle managers, and they probed “say-do gaps” between the behavior they encourage or target to support reliability improvement and the reality of the behavior they tend to see on the front lines (and from themselves). They identified numerous areas of the work climate that were “reinforcing” current undesirable behavior — communication gaps, training needs, lack of clear goals and measures, etc.

New issues are raised

The discussion was losing energy, so we shared some results from their culture and climate survey. We reviewed some challenges related to “listening” and “helping others grow and develop.” It was amazing how these facts re-energized the discussion. The group discussed a coaching initiative that wasn’t going well due to their continual time in meetings and extremely limited time available to coach the front lines. This initiative wasn’t even mentioned during the initial qualitative engagement of the group. They openly discussed how, even when there is time to listen, people are often just listening to support their own agendas. They were probing struggles and culture “elephants in the room” normally covered in sound bites and quick judgments during the normal rat race at work. This time, they were sticking with the discussion and gaining a shared understanding of the current state. It would have been easy to run ahead and fix communications systems, training, or other surface problems originally identified during the first qualitative step, but that wouldn’t have addressed the root cause they were surfacing through a deeper analysis.

The root cause related to an emphasis on just getting production out the door that had persisted for decades, and work to support the reliability priority would not address that issue and the underlying beliefs. They decided to shift their focus to “predictability” improvement: Satisfying production demands at the right time while meeting their quality and safety standards. This focus would require them to shift some misguided beliefs, associated aggressive norms, AND ineffective surface systems, structures and leadership approaches that were reinforcing the current state. The discussions and planning process were difficult but worth it based on the plant manager’s feedback: “This work gave us surgical clarity regarding our problems and what needs to be done to resolve them. It will allow us to turbocharge our plans and results.”

I can’t recall seeing this qualitative-quantitative-qualitative flow recommended in books, let alone the popular press or consulting firm culture whitepapers. I believe it’s the ideal flow for dealing with complex, culture-related problems and improvement efforts, but it’s rarely applied. When it is. it’s often lacking a valid and reliable survey that covers both culture and climate. It’s not a simple flow to facilitate, but it always leads to more targeted and effective problem-solving. It’s messy, hard, and frustrating, but also incredibly rewarding as groups work through issues with a level of shared understanding and clarity rarely achieved in our action-oriented culture.

6. Engage and re-engage team members with discipline to drive shared learning and results

I set up a discussion between Edgar Schein and Robert Cooke. We were recording the discussion on video, but the cameras hadn’t started rolling yet when Ed said, “Culture is built through shared learning and mutual experience.” I thought: That’s it! That’s what I have been working on for 15 years.

I set up a discussion between Edgar Schein and Robert Cooke. We were recording the discussion on video, but the cameras hadn’t started rolling yet when Ed said, “Culture is built through shared learning and mutual experience.” I thought: That’s it! That’s what I have been working on for 15 years.

I never articulated it with such understandable language, but that’s what we were facilitating through numerous group techniques to “unite” our team in support of our most critical performance priorities.

I had been part of many large company meetings before I was promoted to my first VP role. It often seemed like Groundhog Day as some of the same issues came up repeatedly. We wanted to try a different approach and designed a structure for large group “involvement meetings.” I used the same general structure in more than 250 meetings across many organizations.

Each involvement meeting follows a standard structure. Top leadership starts by sharing a general “state of the business/organization.” Groups complete brainstorming and prioritization activities on key areas of improvement for the next 6 to 12 months. Some of these areas are identified or modified based on the results of the culture and climate assessment. Top ideas are captured in documented goals for implementation and tracking. Leadership commits to monitor progress, remove barriers, and recognize positive progress as a team during implementation. A second involvement meeting is held 4 to 12 months later. A major part of the agenda is to review progress from the last meeting, identify what’s worked, and identify what didn’t live up to expectations as a foundation for further feedback and prioritization activities. This disciplined approach unified the team, facilitated shared learning, and helped us improve results. It also allowed us to collectively prioritize some improvements in clear phases from one involvement meeting to the next. Key learnings and best practices were always captured as a basis for application and further improvement in the subsequent phase.

There are countless individuals that just need a vehicle to say what their heart and head want them to say, but they haven’t. They feel powerless to change things. Individuals often feel more comfortable sharing problems and improvement ideas within the safety of a group. A critical step in meaningful culture change is when an unshakable shared belief somehow becomes shakable. The “involvement meeting” structure and other approaches help shake crippling beliefs like, “They don’t listen to us” or “We can’t really impact major decisions.”

The fear of speaking up is a cancer that plagues nearly all organizations. -Tim Kuppler

7. Plan on the ‘resistance’ and learning from it together

We’ve all been there. The resistance can take many forms including criticisms, revisiting decisions, lack of engagement, venting frustrations, lack of follow-up, personal attacks, and perfectionism, where no idea or action is good enough. We live in a culture where encountering resistance is viewed as a problem instead of being a perfectly normal part of any major change. The good news is that we are living in a culture that is establishing new rules for what’s expected in the workplace.

Understanding the resistance and what’s driving it is often the key to understanding culture and the unique struggles individuals and groups encounter. Is it isolated or is it a pattern? Under what circumstances does it surface? Is it a symptom of a deeper issue? What’s reinforcing or encouraging the resistance?

Here are some thoughts on dealing with the resistance:

- Maintain a constructive and positive tone — Ignore that loud and judgmental voice inside your head as you work to learn from the resistance. I listened to a recent culture podcast with Carly Fiorina where she said, “To do anything is to be criticized.” She continued: “We need courage to deal with criticism.” You are doing something that is truly brave when you constructively and positively deal with the inevitable challenges that will surface in any meaningful change effort. Model the constructive behavior you want to see in others and never go negative by getting wrapped up in the resistance yourself.

- Re-group and re-evaluate plans through the lens of culture — Don’t try to deal with the resistance alone as an expert. As Edgar Schein said: “You only truly begin to understand a culture when you try to change it.” The easy thing would be to conclude “that didn’t work” and go back to a less inclusive approach. Re-group and re-engage individuals or groups to deal with what’s surfacing and tackle it as a team. Use it as another opportunity to drive shared learning and adjust plans where appropriate.

- Get used to the culture grind and don’t stop or dramatically reduce change efforts — Thomas Edison said, “Many of life’s failures are experienced by people who did not realize how close they were to success when they gave up.” It’s easy to feel overworked and overwhelmed. We live in a culture where many stop when they experience strong resistance. Expect the resistance. There will be the inevitable anxious or difficult conversations. Plan for it and be disciplined and consistent with your response when it emerges. Empathize with struggles or challenges and clearly identify where plans are being adjusted based on feedback. Don’t dramatically reduce the scope of the work or you will undermine the credibility of the change effort and results.

I’ll end this point with an excellent quote from soccer star Pele:

Success is no accident. It is hard work, perseverance, learning, studying, sacrifice and, most of all, love of what you are doing or learning to do. -Pele

The top three reasons for failed culture transformation

I believe all seven of the insights in this post are incredibly useful in every single significant culture-related change effort, but they do not guarantee success. What differentiates success from failure? I watch for three main qualities, and the absence of one can substantially delay success or lead to complete failure:

- Leadership understands how they are reinforcing the current culture and start by shifting their own behavior. Larry Senn once said, “Culture transformation starts with personal transformation.”

- Leadership is willing to apply an inclusive approach to drive shared learning and results as a team. Many leaders really struggle with the risk and uncertainty of not knowing everything and empowering others to make important decisions.

- Leadership follows a disciplined approach to shift the operating model (systems, structures, habits, etc.) in targeted areas with clarity and speed. It’s a major shift from an organization that struggles with inclusive and united change efforts to one that naturally expects and reinforces them in countless ways.

The common theme with these three qualities is, of course, leadership. Every leader and every change agent is on a learning journey when it comes to culture. The more I understand culture, the more I realize what I still don’t understand. We need a community of culture believers — a support structure to encourage, share ideas, and collaborate to surface approaches and make a meaningful impact.

This post originally appeared on CultureUniversity.com.