Let’s be honest, HR is supposed to prevent hard-to-control managers from saying stupid things in interviews. We all know what is happening: the manager wants to entice the prospective employee to come work for the company; some will make promises that HR knows the company won’t keep. Unfortunately, these exaggerations can open the door to a lawsuit with claims called fraudulent inducement and promissory estoppel.

This article is all about how HR can prevent these lawsuits.

First, some credentials – I’m an employment lawyer. From your perspective, I’m the bad-guy. I represent employees. I’ve sued plenty of companies and deposed HR many times and recently settled a fraud in the inducement case. I made a YouTube video about CA’s law on the matter and dedicate an entire page on my website to it. I’m actively looking for these cases. So, if you don’t want to see me or one of my colleagues in court, pay close attention to what I’m about to say.

plenty of companies and deposed HR many times and recently settled a fraud in the inducement case. I made a YouTube video about CA’s law on the matter and dedicate an entire page on my website to it. I’m actively looking for these cases. So, if you don’t want to see me or one of my colleagues in court, pay close attention to what I’m about to say.

Employment cases are increasing

Fraud in the inducement claims are on the rise. Our workforce is mobile and people change jobs a lot. Anecdotally, my office has handled more consultations regarding fraudulent inducement and promissory estoppel in the past few months than at any other point in my career.

I’ve written this article to help HR professionals better understand the issue and prevent it from happening in the first place.

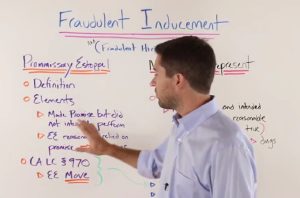

What is fraudulent inducement?

While specific statutes barring companies from engaging in fraudulent inducement differ from state-to-state, the practice typically begins with a company making an offer of employment.

This offer might involve a company courting a prospective employee by promising a high annual salary. Then, after the employee moves to take the job, she suddenly finds that checks are far lower than what was agreed upon.

In most states, the law distinguishes between two types claims:

- the first is known as promissory estoppel. This involves an employer who makes fabricated promises during the hiring process, and does not intend to perform on these promises.

- The second is known as negligent misrepresentation. This involves an employer making a promise and intending to follow through, but the employer had no reasonable grounds for believing that promise to be true.

In both types, the employee must reasonably rely on the promises made to his or her detriment.

These claims are alive and well across the country. The Texas state court of appeals has considered a number of different promissory estoppel cases. In NY, these claims are difficult to win, but are still viable. California has a powerful double-damage statute that gives real teeth to these claims.

Regardless of your state’s law, it’s important to remember that even a preliminary hearing resulting in summary judgment in favor of your company can mean massive legal bills. So, it’s always better to prevent these claims from arising in the first place.

As Benjamin Franklin said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

A real world example

A great example of this type of case was detailed in a Medium article written by Penny Kim. In the article, Kim describes her brief experience working for a Silicon Valley startup in 2016. During the hiring process, she was promised a marketing budget of $4 million and an annual salary of $135,000, along with a $10,000 signing bonus.

Living in Dallas at the time, she packed up her belongings and moved to Silicon Valley to begin her new career. After some ominous red flags during investor meetings her first scheduled pay check arrived late.

Kim’s next check, the one that was to include the signing bonus, was late and missing the bonus. After several days of waiting, she received an email from the CEO saying he would transfer money directly into her account. As proof of the transfer, the CEO included in the email a forged image, digitally altered to look like a wire transfer confirmation.

Eventually, it became clear that her employer didn’t have the money to pay the employees (and never had it to start with). Kim filed a claim with the state labor department, and was ultimately fired.

Since the publication of her story in Medium, and a follow-up by The New York Times, the United States Department of Justice announced it had indicted the company’s CEO on five counts of wire fraud. Oops.

Three takeaways for HR leaders

Ms. Kim’s case illustrates how a charismatic founder and CEO can destroy the future of an entire company by making false promises. While the case may be an extreme example, hiring managers often make claims about the company that are more wishful thinking than true, and they make promises they know they don’t have the power to keep.

Here is what HR can do about it:

1. Train your hiring managers well

This involves sitting down with the hiring manager and telling them about fraudulent and negligent misrepresentation. It is very important the company only makes promises that management knows it can keep. By the way this is also a great time to tell them not to ask about race, religion, age, national origin, etc.

2. Speak-up during the interview!

HR reps must speak-up to check company execs that are playing fast and loose with facts during interviews. If an executive says something that isn’t true (or that is really gray), interject and make sure the record is straight in that interview. It’s better to miss hiring an excellent candidate than it is to hire an excellent candidate and then get sued.

3. Double-check the offer letter

What is in writing is what will be used against you, so double-check that the offer letter is 100% accurate and contains no false or gray promises. You’d be amazed how often I find profoundly misleading statements in offer letters.

When it comes to determining if there is a problem or not, don’t ignore your instincts. You may not be the CEO, but you’re a vital part of the company, and know as much (if not more) about what kinds of hiring decisions the company is in a financial position to make.

I know it’s not always easy to let the company know that it’s treading in dangerous legal territory, especially when the future of the company is uncertain and nerves are already frayed. But again, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.