Editor’s Note: It’s an annual tradition for TLNT to count down the most popular posts of the previous 12 months. We’re reposting each of the top 30 articles through January 2nd. This is No. 19 of the 800 articles posted in 2018. You can find the complete list here.

∼∼∼∼

Going from one reality to another frequently presents challenges. Women returning to work after an absence (most notably after having children), experience a unique set of challenges. I’m coining the manifestation of these challenges “Return to Work Syndrome.”

Return to Work Syndrome is a culmination of the fear, worry, shame, confidence loss, and trepidation women experience when returning to work after a prolonged absence. The most common absence women experience is one resulting from childbirth and motherhood. However, Return to Work Syndrome isn’t specific to mothers. It also applies those returning to work after absences stemming from job loss, chronic illness or family medical leave, active duty service, extended bereavement, and a change of personal or professional direction.

A good way to frame Return to Work Syndrome is to begin with reentry.

Reentry is defined by Merriam-Webster as follows: “a second or new entry.” Often, we think of reentry as a major event or transition between one reality and another. A common example of reentry is soldiers returning to civilian life (and vice versa). In fact, some mothers may consider returning to work life after motherhood as parallel — and just as challenging — as a soldier’s transition to civilian life after combat.

Major life transitions like returning to life that was once familiar can bring about anxiety, fear, apprehension, dread, and unease. Women who reenter the workforce after an absence experience the same.

Also, it seems that regardless of a mother’s standing, no one is immune from Return to Work Syndrome. Khloe Kardashian, posted a video on Snapchat expressing anxiety about returning to work after maternity leave. She stated, “I have missed a feeding here or there with True… but I’ve never missed multiple feedings in a day, so I have a ton of anxiety.”

Some companies are coming up with unique ways to help new mothers return to work. See “Top Companies Are Making Life Easier for New Parents With Unique Programs“

In addition to general anxiety over the transition, women are also challenged with a general lack of confidence in the skills and abilities not used during their absence — or they may not have used their skills and abilities in the same way while away from the work force. It may even feel as if they’ve lost their edge while pursuing other things.

Questions and phrases like, “I haven’t been doing anything for the last [10] years, what skills can I offer?” and “I used to enjoy a good salary, but things are different now,” and “I’m so much older than all the other applicants, what value can I bring?” plus “How can I catch up to today’s technology?” and “I’ll just start over,” may go through their mind.

Mothers pay gap is worse

What’s worse, those fears are evident when women look for work and negotiate their salary. It’s not just fears either, the corporate environment (in the U.S. at least) pays women less than men, mothers less than fathers, and mothers less than women who don’t bear children.

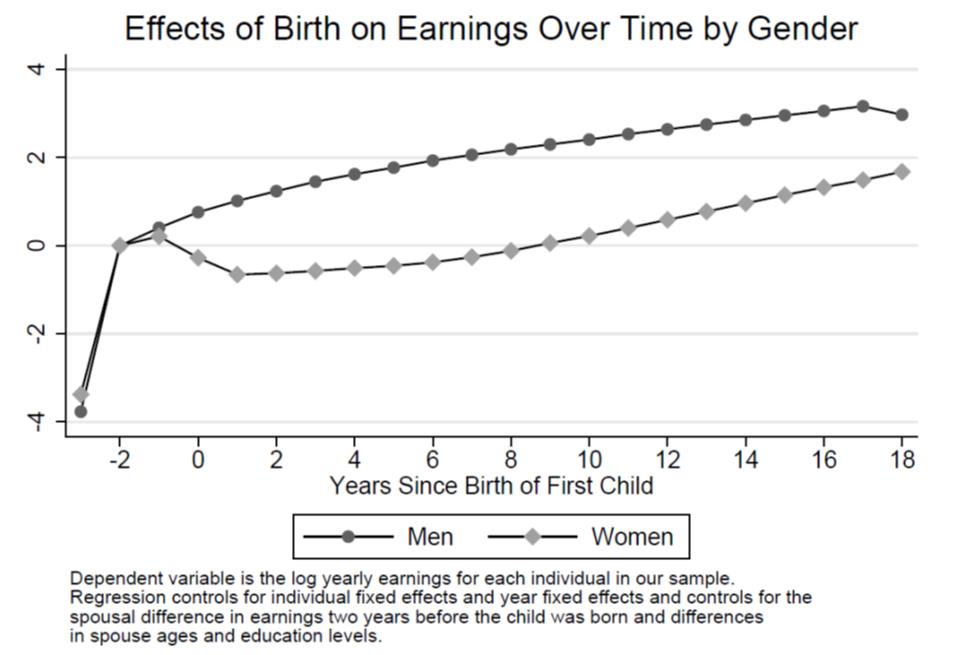

In November of 2017, the US Census commissioned a report, The Parental Gender Earnings Gap in the United States to examine the earnings gap in parents before and after the birth of a child. The results are staggering.

According to the study:

“The main shock at the time of the birth of the child is experienced by the women, whose earnings fall at the time the child was born. They do not recover until the child is 9 or 10 years old. Since the earnings of the male spouse do not undergo the initial shock, the wage gap between the two genders never recovers.”

The earnings gap is one of the harsh realities women face and it’s where the “Syndrome” part of returning to work comes in. I see Return to Work Syndrome impacting women in three ways:

First, there’s the “maternal wall,” introduced by Deborah J. Swiss and Judith P. Walker, Women and the Work/Family Dilemma (1993) as “the motherhood equivalent of the ‘glass ceiling’ that all women face — that is, the inability to advance in their careers based on stereotypes of mothers’ abilities and commitment to work.” The fact is, employers see mothers as less capable to perform, produce, and remain committed to work than others, even though a 2014 Federal Reserve study, as reported in the Washington Post, “found that over the course of a 30-year career, mothers outperformed women without children at almost every stage of the game. In fact, mothers with at least two kids were the most productive of all.”

Second, the “imposter syndrome,” coined by Dr. Pauline R Clance and Suzanne A Imes in 1978 refers to a phenomenon where high-achieving individuals are plagued with an inability to embody their accomplishments and are haunted by thoughts and fears of being found out as a “fraud.” Essentially, individuals suffering from imposter syndrome don’t own their achievements. This often results in anxiety and ongoing fears.

Third, when you combine the apprehension women have about transitioning to a new reality of returning to work, with a lack of owning their worth, and a system that limits their earning potential over time, women become confused, stuck, and passive in their job search.

Two other limiters

A recent study explored two additional circumstances that compound the place mothers come from when preparing to reenter the workforce. The first is “skill deterioration theory,” which argues that those with a break in employment aren’t as valuable others who were continuously employed because those absent for a period weren’t actively utilizing their skills, which deteriorate (or even become obsolete) from lack of use. The fear for employers is those without recent experience will require additional training.

The second is “signaling theories” which notes a job candidate’s employment history “signals” information about the candidate, and employers use these details to make assumptions about the employee. Further, tests of signaling theories have proven a period of unemployment scars job applicants and results in fewer job opportunities.

When reporting the results of the study in “Stay-at-Home Moms Are Half as Likely to Get a Job Interview as Moms Who Got Laid Off,” researcher Kate Weisshaar asserted, “Put simply, stay-at-home parents were about half as likely to get a callback as unemployed parents and only one-third as likely as employed parents.”

Coming from a less than empowered place makes it nearly impossible for women to assert themselves, communicate and demonstrate their skills effectively, all the while asking for what they deserve (in terms of salary and benefits), and more.

Mothers more productive

In the Washington Post article, writer Ylan Q. Mui summed it up this way:

“Mothers tend to be more productive both before and long after the birth of their children. When that work is smoothed out over the course of a career, the (Federal Reserve) paper found, they are more productive on average than their peers.”

Regardless of the reason for the absence, the period of time away from the workforce, and a candidate’s motherhood status, the effects of Return to Work Syndrome are profound. But they can be minimized through effective networking, sharp resume presentation, preparedness for interviewing, and most of all by demonstrating confidence and competence when presented with opportunities to break through their personal glass ceiling.