We like our leaders confident. Confidence is the leader’s best friend, the one attribute no leader can be without; the keys to the kingdom.

There’s no shortage of material on how to be a confident leader and find out the secrets of confident leaders in business and history. And there are plenty of gurus and business leaders who will show you the path to greater confidence – for a fee, of course.

This focus on confidence isn’t surprising; psychological research tells us that people who sound more confident and more authoritative are generally listened to and believed in more completely. If you are running a business, setting yourself up as an expert, or running a political campaign, it pays to speak and act confidently.

Overconfidence leads to poor decisions

Unfortunately, confidence is not the same thing as ability. Even confident people make mistakes, and the more confident they are the bigger those mistakes may be. Way back in 1876, Western Union turned down a patent on the telephone (it had “no commercial possibilities” given the ready availability of messenger boys). More recently Kodak invented the digital camera but then did not push it forward (it could have cannibalized their film business), Lehman Brothers borrowed massively just before the bubble burst… I’m sure that you can fill in your own examples. With the benefit of hindsight, the mistakes are obvious. At the time, however, these likely seemed like sound decisions, and are a reminder that we are all prone to biases in our decision-making.

When it comes to leadership, one of the most important biases is the “overconfidence effect”; our abilities don’t always match our self-confidence. For example, do you consider yourself to be an above average driver? If you said no, you are in a minority. Even though, objectively, half of any large group of people should say yes and half should say no, a 1981 study found that 93% of US drivers said they were above average.

The less we know the more confident we are

Overconfidence has contributed to some of the worst errors in leadership decisions. The less we know about a subject, and the less ability we have in an area, the more confident we are in our ability and our decisions, a phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. We want our leaders to be confident in taking calculated risks, but unfortunately they are likely to make the rashest and most overconfident decisions in those areas where they have the least knowledge and ability. Ambitious, grandiose projects outside of their sphere of expertise may be approved with little discussion; projects closer to home are scrutinized minutely.

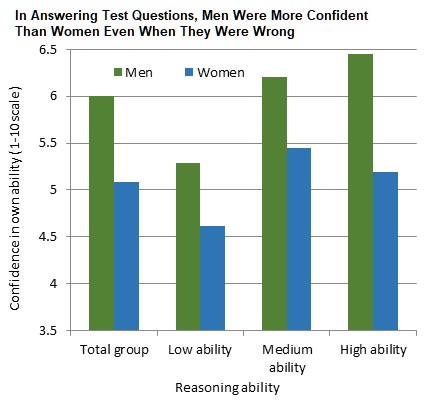

The negative effects of overconfidence are often exacerbated by groupthink, where any data or dissenting voices that are inconvenient to the story constructed by the leader are ignored. Public enquiries and other post-mortems of failed projects typically show that concerns were voiced early on but then not listened to; often those sounding the alarm were sidelined or pushed out. Leaders can become hubristic, believing that only they have the answers, ignoring any signs that things are going wrong until it is too late. There is a whole research literature devoted to hubristic leadership and narcissistic leadership, demonstrating that not only do such leaders not listen to others, but also that their presence stifles discussion and exchange of information in their team and even across the organization. When a crisis hits, this reluctance to listen to other voices can lead first to a denial that things are going wrong and then to an inability to come up with alternative solutions.  No one had dared to think of, much less discuss, the possibility of failure and so no one had thought of any new ways forward. In a further twist, research has shown that men are more likely to be overconfident about their abilities than women, even when women have an objectively higher level of ability.

No one had dared to think of, much less discuss, the possibility of failure and so no one had thought of any new ways forward. In a further twist, research has shown that men are more likely to be overconfident about their abilities than women, even when women have an objectively higher level of ability.

The antidote is self-awareness

I’m painting a bleak picture here, but there is a way out: building self-awareness. By becoming more aware of their personality, behavioural style and biases, individuals can make informed decisions, helping to overcome the pressure to follow groupthink, and leaders can gain a clearer view of their own limitations and see the value in alternative viewpoints.

People with a more accurate self-perception perform better in the workplace; for example, a study carried out in the Royal Navy found that more self-aware leaders were better able to tailor their leadership style to the situation at hand. Better employee performance plus more agile leadership typically leads to a better bottom line.

However, while most people believe they are self-aware, research by The Eurich Group shows that self-awareness is actually in short supply, with only 10-15% of people truly self-aware. Fortunately, there are many ways in which leaders can enhance their self-awareness – coaching, for example – but one of the most cost-effective is the use of personality questionnaires. These can provide a framework for an individual to understand themselves and why they behave in the way that they do, and then to build on this to see how they are different from others and how these differences can be used on a positive way. From the knowledge of how their personality interacts with others on a one-to-one basis, a leader can build to understanding how they can work more effectively with teams, departments, and organizations.

We live in a time when confidence, or at least the appearance of confidence, seems to be rewarded for its own sake, and where unreservedly positive thinking can be prioritized at the expense of a cool appraisal of reality. It is all the more important, then, that business leaders do not mistake confidence for reality, and avoid the siren call of groupthink.