All this week, TLNT has been talking about the one big HR issue of the moment – return to office (RTO) mandates.

Not a week seems to go past without one employer or another going hard-ball on staff, and turning their polite return request into an out-and-out demand – with an accompanying ‘or pay the consequences’ threat (subliminal or overt).

It’s why Mark Murphy this week talked about the hypocrisy of RTOs from a leadership point of view, and why we yesterday case studied one digital marketing agency taking a very different approach.

To really round this topic off though, today we’re looking at what the real impacts of an RTO can actually have on talent retention – something that’s often speculated, but rarely actually substantiated with any hard and fast data. Until now that is.

Gartner has just released some brand new research which looks into the so-called ‘flight risks’ (ie people quitting), when companies institute a RTO policy.

It took its regularly used ‘intent to stay’ questionnaire and compared the results of this between companies that had mandated to return to the office and those who had not – and with some very striking results.

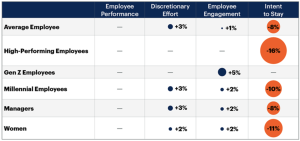

The headline figure was that intent to stay amongst average employees was a whole 8% lower with strict RTO mandates, and it was higher still amongst women and Millennial employees.

“We wanted to understand the implications of onsite work requirements on talent retention, because it’s still the case that there is division within companies, and even between different management teams about what is right path to tread,” says Caitlin Duffy, director in the Gartner HR practice, speaking exclusively to TLNT.

She added: “Managers – who grew their own careers in an office environment, and who are still uncomfortable with the concept of fully remote working – are wanting to know what the impact a decision to require people to return will have. Until now, there hasn’t really been this.”

So what of the results?

The summary table can be seen below – showing that overall, in companies that operate a strict RTO, stated intent to stay decreases by 8%. Amongst Millennial workers intent to stay worsens still, down 10% – which is perhaps not as high as one might expect – and amongst women it’s the most, down by 11% [we’ll talk about discretionary effort in just a moment].

“We kind of suspected that intent to stay figures would decrease – because other studies repeatedly show staff say they want ever-more autonomy and flexibility – but now it’s possible to put an actual figure on this,” says Duffy.

She adds: “The fact Millennial staff aren’t dramatically more likely to leave may sound surprising, but this is probably consistent with the fact that younger people – many of whom may be in their first ever job – value creating social connections and making friends, and enjoying the outside-hours aspect of working with people. Women being the most turned off by RTOs also makes sense, if we consider many have care responsibilities.”

So we’ve got the data – but now what?

A second standout fact is that it’s high performers that exhibit the greatest reduction in intent to stay – falling by a whopping 16%. In other words, it’s double the pain of an average employee quitting.

But now that this data exists, it arguably presents even more questions than it does answers. Like, what if HR is actually happy with an 8% quit rate (maybe they think it’s their less engaged staff that will go), and that losing some of the ‘dead wood’ is a risk worth taking if it means their bringing people together (with all the better collaboration that’s known to take place) is achieved.

“I think what our data is saying, is that now we’ve found out what we have, every organization needs to make their own interpretation of it,” suggests Duffy. “There maybe other things that CHROs think has a greater impact on retention that RTOs, and so they may decide to enforce a return anyway, and hope for it having only a minor impact.”

But, she adds: “What I would say, however, is that if CHROs expect ‘some’ talent to go, our data suggests they’re more likely to lose their ‘best’ people first – which definitely won’t be the outcome they may want. The impact of this isn’t just the top talent going, but how this impacts the talent pipeline thereafter, so in this case an RTO might present itself as a big risk.”

Is ‘intent to stay’ meaningful though?

The biggest question, of course, is that ‘saying’ they’ll quit might be one thing, but whether they actually follow through with this is quite another, and CHROs might want to take the calculated guess that this could all just be bluff, and it won’t really amount to anything.

There is plenty of new data with suggests this could be true. Quit rates were recently revealed to have dropped rapidly, to a decade-long low; indicated staff may not be so gung-ho about threatening to leave if push comes to shove. There has also been the suggestion recently that ‘layoff anxiety’ is now a real thing, and sensible staff are those that keep their heads down and stay put.

“It’s absolutely the case that family, schools, community and other ties prevent a lot of people from being able to up-sticks,” admits Duffy. “The question is, can CHROs risk calling their bluff?”

Acting as a pack?

What has been certainly commented on, is the fact that if ‘all’ companies decide to enact mandatory RTOs, then employers effectively gain safety in numbers. If everyone has an RTO, then disillusioned staff won’t actually be able to leave to go somewhere better at all, because they’ll also have to be in the office if they move elsewhere.

“Intent to stay is different to actual attrition, but even here, I’m not sure this would be a good strategy to follow,” says Duffy. “It’s still the case that when people are ‘looking’ to leave – even if they’re not actually leaving, they’re still unlikely to be the greatest contributors – engagement will be low.”

This brings us neatly to the column in the table above which on the face of it, doesn’t seem to look right – the finding that people who have lower intent to stay actually give more discretionary effort (the data shows this rises between 2-3% when an RTO is issued. This is not what one would expect.

“I think what these figures are telling us, is that effort might go up, because people feel like they’re being monitored more when they’re in the office, and so staff have to ‘look’ the part of being busy,” argues Duffy. “The point I would make though, is that while this might be so, it’s debatable as to whether this extra effort translate into real additional performance.”

Conclusions

So what can we really conclude here?

It’s seems quite clear that if companies are going to decide to implement an RTO, they’re going to have to accept that people might leave; that it will be their best people who will leave; and even if they don’t leave, staff are unlikely to be that happy about it.

The real dilemma is whether bosses think some short-term disquiet, that may well dissipate is still worth it.

Firms are clearly issuing RTO mandates because they still believe working in an office is more productive, creates informal learning, improves collaboration and team work, improves culture, and ultimately creates the sort of serendipity that being on the end of a pre-booked Zoom call doesn’t. These are all noble wants, and maybe leaders shouldn’t be admonished for wanting this.

“I think that if this research says anything, it’s that firms at least need to be much more intentional about why people should be in the office – ie for what purposes is it best, and for what purposes, or for which teams, or for which stages of projects remote working is perfectly sufficient,” says Duffy. “When this sort of stuff moves beyond policing, and to finding out the best ways of doing things, that’s when being in the office becomes wanted and needed rather than disliked and resisted.”

TOP TIPS:

Gartner has identified four best practices HR leaders should consider if their organizations seek to formalize in-office work requirements:

1) Motivate employees to return to the office rather than mandate:

Organizations can motivate employees to come to the office by designing their office space and hybrid policies to make employees feel capable, autonomous, and connected.

2) Consider policies that focus on-site attendance per year, not per week:

Gartner research found that organizations mandating a minimum number of in-office days per year achieve greater employee performance than those mandating a minimum number of in-person days per week.

3) Enable employees to shape the RTO policy:

Employees who contributed to their teams’ hybrid work arrangements and felt like their needs were considered demonstrated both higher engagement and work performance.

4) Provide a clear reason behind requirements for working on-site:

Organizations that transparently communicated their reasons for wanting employees to come into the office saw positive impacts on engagement, discretionary effort and retention.