When you think about our current economy you probably evaluate that we’re in a recovery period, a time in which the job market is slowly – very slowly – on the mend.

You probably imagine employment rates on the rise, and would claim we’re faring considerably better than we were during the recent recession. And you’d be right.

But for one group in our nation, this holds hauntingly, troublingly, untrue, and we need do our darndest to figure out a solution because this is one important group of people: they are our future.

Steep drops in teen employment rates

A recent report by The Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University and JAG (Jobs for America’s Graduates) examines in detail the employment outcomes of high school graduates from the class of 2012 who did not enroll in college, and the results were not positive.

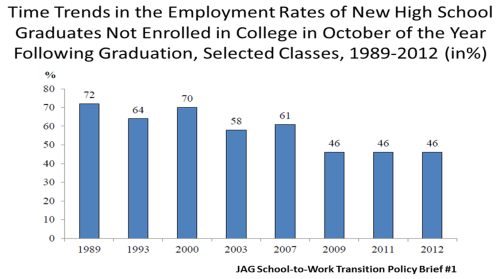

Employment rates for our nation’s teens over the last several years (all demographic, socio-economic, and schooling groups) have seen steep drops. These drops have been so steep that employment rates for teens have reached new historical lows for the post-World War II period.

High school students and young high school drop-outs have seen the greatest differences in securing paid employment (of any type) in recent years and young high school graduates, especially those not enrolling in college in the fall after graduation, have seen both declining employment rates and a strongly reduced ability to secure full-time work.

Lowest teen employment rates since 1959

What’s concerning is the nature of these drops. Until recently the ability of America’s teens to obtain work has been fairly cyclical, with teen employment rates rising to above average during periods of job growth and falling during periods of recession.

During the economic recovery of 2003-2007 however, teen employment rates did not see any significant rise, dropping from a rate of 70 percent in 2000 to 58 percent in 2003 and recovering only 3 points to 61 percent in 2007. Employment rates failed to increase again during the current job recovery from the recession of 2007-2009, dropping from 61 percent in 2007 to 46 percent in 2009 and holding there in both 2011 and 2012.

These are the lowest employment rates for new non-college enrolled high school graduates in the U.S since the data series began being recorded in 1959.

The employment rates of high school graduates varied considerably by gender and race ethnic group and across the board male high school graduates fared worse than female graduates, their employment rates dropping to an all-time low of 44 percent in Oct. 2012. Family income also influenced employment rates, with high school graduates coming from higher income families (no surprise here) seeing a stronger likelihood for employment.

Another important note though, is that the ability of employed high school graduates not attending college to obtain full-time jobs has also declined dramatically since 2000. This number dropped to 43 percent in October 2012, the lowest full-time job share ever recorded in this data series.

A large-scale labor market issue we need to address

The report combined the findings on the employment rates of non-college enrolled high school graduates with the share of the employed working full-time to calculate their employment to population ratios, which are consistent with the declining employment statistics and darker still.

In the month of October 2012, only 19 of every 100 high school graduates who did not attend college in the fall were employed full-time, another historical low. As this study implores us, we need to think about the message and implications of these unemployment rates.

Not only will this lack of employment adversely affect the future of these graduates in terms of lower employment rates, wages, and reduced training from employers, but it also sends the wrong message to youths still in school.

How can we expect young people to understand the value of a high school degree, and support our claim that it’s important to stay in school, when their direct experience is observing the many idle graduates (their peers) with no employment and nothing to do? As of now, no new policy initiatives exist to address this large-scale labor market issue.

So it’s up to us. What are we going to do about it?

This originally appeared on China Gorman’s blog at ChinaGorman.com.