Judging by most of the recent published data and countless other news reports about people’s incomes, it’s fair to assume that wages have – on the whole – been rising.

A recent report from The New York Times announced that that by November 2023 real incomes had increased 2.7% above their January 2021 levels.

The Wall Street Journal, meanwhile, reported that: “Real after-tax incomes rose 3.8% in July from a year earlier, and have risen year-over-year each month since January.”

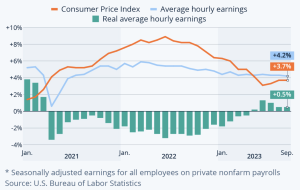

Finally, a Bureau of Labor Statistics press release recently included this line: “Real average hourly earnings increased 0.8 percent, seasonally adjusted, from November 2022 to November 2023.”

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics also recently concluded real wages had risen, now that average earnings had once again risen higher than inflation (see below):

And yet, here’s the thing: People just don’t seem to believe it.

In a recent nationwide poll, more than 80% of people described the condition of the economy as fair or poor, and only 19% called it good or excellent.

A majority described their personal financial situation as bleak, citing inflation and stagnant income. This was despite the rate of inflation having dropped to around 3% and the labor market remaining very tight.

So why the disconnect?

Lies, damned lies, and statistics

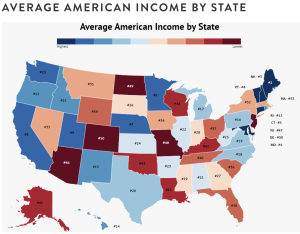

Source: zippia.com

The quote above, attributed to Mark Twain, has been described as one of the best critiques of applied statistics.

It can also be an explanation of the situation regarding the disconnect between the public’s perception of income and wages and the actual data.

Let’s examine this in more detail:

Claims that wages are rising draws on data from the BLS, which measures average hourly earnings.

The key here is “average”. The BLS measure is heavily influenced by the composition of the labor force.

When Covid-19 lockdowns forced people into unemployment, large numbers of those working in service jobs were disproportionately affected.

The leisure and hospitality industries, for instance, shed millions of jobs, many of which have not returned because the businesses that employed them shut down permanently.

This industry is still short of more than half a million jobs (and workers) compared to the levels that existed before the pandemic. With millions of people having left the workforce, the industry may not recover to pre-pandemic levels for years.

The problem here is that these lost jobs were typically low-paying.

The impact of this was to raise average earnings.

That is, average earnings increased because there were fewer low-paying jobs, not because people in the workforce started earning more.

As these jobs have started to return, the rate of growth of average hourly earnings has started to slow. Again, this is a statistical change, not a fundamental aspect of the economy.

The BLS has another measure of earnings – the Employment Cost Index (ECI).

This measures the change in the hourly labor cost to employers over time.

The ECI uses a fixed “basket” of labor to produce a pure cost change, free from the effects of workers moving between occupations and industries.

That is, the ECI is a measure of income adjusted for inflation.

Looked at this way, wages and salaries have fallen by about 3% since the start of the pandemic.

Analyzed over a longer period, inflation adjusted wages today are about where they were in 2016.

It’s no wonder that people are unhappy about their earnings and see their financial picture as bleak.

‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help’

Efforts to change this situation are not encouraging.

California passed a law raising the hourly minimum wage for fast-food workers to $20, from the present $16.

This was done with the goal of helping these workers cope with the rising cost of living and inflation in the Golden State.

In advance of the law taking effect, the fast-food industry has started to shed jobs. Other fast food purveyors have announced plans to raise menu prices. Who could have seen that coming?

Without really big increases in productivity, real wages are unlikely to rise much.

The wage for any job typically reflects the value of the work done, and improvements depend on gains in productivity.

So attempting to force an increase in pay by legislative shenanigans will not help improve the situation, and may well have the exact opposite effect as demonstrated in California.

But there’s no mystery as to why people are disgruntled about their economic situation.

Effectively, they are no better off than they were seven years ago.