Unions are quite rightly dominating the news just now.

Most recently, some 10,000 United Auto Workers (UAW) members have staged strikes that – in just a few weeks, are already having a crippling impact on hree automakers (Ford, GM and Chrysler parent, Stellantis.

Then we’ve had the writers and screen actors, who have been on strike for months, decimating film and TV production and leaving cinemas wondering whether they’ve got anything to put on next year.

A few weeks ago, unions won big pay increases with threats of a strike at UPS. In the last few years, some 350 Starbucks stores have unionized for the first time – oh, and let’s not forget that even workers at the dinner-theater chain, Medieval Times, are on strike demanding improved castles and pay increases for knights, stablehands and trumpeters (kings and queens were not mentioned in the strikers demands).

As well as this on-the-ground activity, we’re seeing government also working in overdrive, to support of the President’s campaign promise to create millions of “good paying union jobs.” Aides are pushing for the passage of the PRO (Protecting the Right to Organize) Act and there is also an executive order mandating union pacts for federal projects over $35 million.

Notwithstanding all of this, the National Labor Relations Board is putting its thumb on the scale at every possible opportunity, to make it easier for unions to organize new groups of workers.

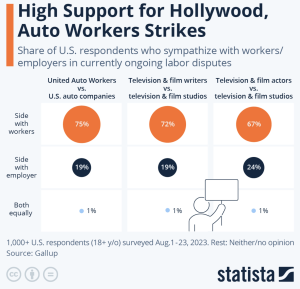

Public opinion favoring unions has also surged with 67% of respondents in a recent Gallup poll supporting strikes.

Inept, unproductive and disengaged

In the midst of all this, and with the very real spectre of further economic uncertainty, one ought to expect that union membership would be surging.

But the reality is that union membership continues to decline, now at just 10.1%, which it down from 11.3% ten years ago.

Workers in private industry are 6% unionized, down from 8.6% two decades ago.

For public employees, it’s 33.1%, down from 37.3%.

So what’s behind the decline?

Unions have had the occasional victory – such as the one at UPS, but by and large they have proved to be remarkably ineffective.

Of the 350-plus Starbucks stores that have unionized, not a single one has managed to get a labor contract with the company.

Unions can also be their own worst enemies, with their leadership often being divorced from reality.

When the trucking firm, Yellow Freight, was struggling financially and asked for wage and benefits concessions from the Teamsters Union that represents its employees, the Union President Xed (tweeted) the image of a gravestone with “Yellow” on it.

How prophetic. Yellow Freight has since filed for bankruptcy, which could lead to more than 22,000 Teamsters members losing their jobs.

More disasters could follow

The strike at the three automakers could also prove disastrous too, with the UAW demanding a 32-hour work week and a 40% increase in pay – something that appears to many to be on the fringes of what is reasonable.

GM’s president, Mark Reuss, has already gone on record, saying such extensive pay rises are “untenable,” and it’s worth noting that the three automakers have actually proposed 20% pay rises over the next four and a half years.

These – arguably generous-looking rises – have been rejected.

The main beneficiary in all of this will be Tesla, which is non-unionized and already has a big cost advantage. Labor costs for union workers at the big three amount to more than $60 an hour, compared to $45 at Tesla.

Any gains the UAW makes will only further erode the competitive position of the big three automakers – brands that have already been losing market share for decades.

Productivity isn’t improving

But the biggest reason unions are finding it so difficult to win concessions from employers is because they consistently prove they don’t improve the one thing most employers want: productivity.

In union intensive industries, such as car manufacturing, productivity is abysmal.

Over the last ten years, it has fallen by 32%.

This is well below the rate for the economy as a whole, where it has grown by 14% over the same period.

This may partly be attributed to a lack of engagement from union workers.

Data shows that workers who are union members are less engaged at work (27%) than non-union members are (33%).

Furthermore, about a quarter of union members (24%) are actively disengaged at work, compared with 17% of nonunion workers.

Actively disengaged employees are not just unhappy at work; they tend to be resentful that their workplace needs aren’t being met, and often act out their unhappiness.

The other reason for low productivity is a lack of automation, which is frequently resisted by unions.

The US has 274 robots per 10,000 workers, while China has 322.

South Korea has – wait for it:1,000.

Given that the US is a high-wage economy, the only way manufacturers can compete is to boost productivity, which requires increasing automation.

A changing reality

There’s little to suggest the decline in unionization will abate.

The economy continues to move away from sectors that were traditionally union strongholds – industries like manufacturing, transportation, and construction – represent a shrinking share of the workforce.

Union plans to expand into the service sector may not bear much fruit either.

Labor laws require unions to organize specific workplaces, which are much smaller in the service industry.

This increases the logistical difficulties and costs for unions to organize.

The 350 plus Starbucks locations that have unionized represent barely 2% of the 16,000 plus stores that the company has.

And it’s worth remembering one other important fact too: Public support for unions is mostly virtue signaling.

Although support seems outwardly very high (see above), Gallup found that most non-union workers have little or no interest in unionizing.

While many union members truly value their participation, those who are not members don’t generally feel they are missing out, with only about 11% being interested in joining a union.

A majority of nonunion workers (58%) have no interest in doing so.

If there’s a silver lining here, it’s hard to see.