The number of Americans receiving medical coverage through Health Savings Accounts (HSA) in tandem with a high-deductible health plan (HDHP) has skyrocketed in the last decade. (An HDHP is a health plan that satisfies certain requirements for minimum deductibles and maximum out-of-pocket expenses.) Generally, under Internal Revenue Code Section 223, an HDHP may not provide benefits for any year until the minimum deductible for that year is satisfied. This means that, with limited exception for specifically-defined preventative care coverage, individuals are broadly required to absorb all first dollar medical costs before HDHP coverage can begin.

HSA critics have long-complained that this requirement unfairly impacts individuals with certain chronic ailments. Now, in what should deliver a helpful injection of flexibility to promote HSA usage, the IRS has expanded the list of items that can be covered on a first-dollar basis under a high deductible health plan (“HDHP”) to help treat certain chronic health conditions.

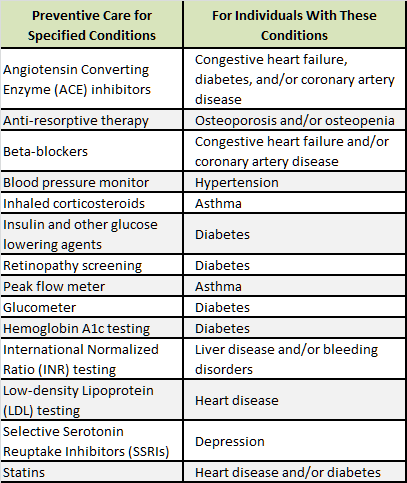

In Notice 2019-45, the IRS included the following list of prescription drugs and medical devices that can be covered before the participant reaches the deductible if they have been diagnosed with the applicable condition listed in the chart.

Although this change became effective last summer modification of the plan can be made any time, although doing so at the plan anniversary represents a much easier path from an administrative and operational perspective. Employers choosing to adopt the rule at any time other than the plan year anniversary would be inviting the added administrative operating burdens of possibly accommodating mid-year plan changes in accordance with often tricky IRS cafeteria plan change-in-status rules.

Plan sponsors should note two crucial takeaways from the new IRS guidance:

- Exclusivity. Only those items listed in the left hand column can be covered first-dollar. Moreover, they can only be covered first-dollar if the covered person has the corresponding medical condition in the right hand column.

- Discretionary. A plan does is not required to cover these items on a first-dollar basis. The IRS specifically said these are not required preventive care services as defined and mandated under the Affordable Care Act. However, a plan has the authority to cover all, some, or none of the conditions (named above) before the plan’s deductible is reached.

This guidance was released, in part, in response to a Trump Administration Executive Order issued early last year. Historically, treatment of a current condition was not viewed as “preventive” by the IRS. However, in the Notice, the IRS says that keeping these conditions under control helps prevent further, more expensive complications from developing.

Next steps

An employer that wants to implement the option to expand the range of covered services as permitted under Notice 2019-45 should keep a few points in mind.

- Update plan document — The employer must work with its insurer (for insured plans) or plan document provider (for self-funded plans) to update the plan document. Current group health plan documents typically include restrictive language intended to satisfy earlier IRS standards for HSA operation. Consequently, unless the plan document is updated to specifically name any of the newly expanded types of chronic care benefits and limits coverage to those with corresponding qualifying medical conditions, delivering such benefits raises the specter of ERISA and HSA violations.

- Summary of benefits and coverage — Employers making changes to accommodate individuals with chronic conditions will likely require an updated SBC. An updated SBC appears unavoidable as one of the mandated SBC examples includes an individual managing his Type 2 Diabetes and describes the costs involved. If a plan adopts the changes related to diabetes, then that example is likely out of date. Other aspects of the SBC may also require changes. The updated SBC would need to be distributed at least 60 days before the change is effective. (However, the 60 day advance notice SBC rule can be avoided if the plan sponsor defers a change to comport with Notice 2019-45 until the next plan year anniversary. Often plan sponsors will elect to group, consolidate and then pend all SBC-impacting changes until the plan anniversary date and then simply issue the new SBC to accommodate open enrollment season.)

- ERISA-directed disclosures — The employer must update any summary plan descriptions to include these new services. Most employers will use a “summary of material modification” (SMM) for this purpose. Note that since changes to comport with Notice 2019-45 represent benefit improvements the employer has ample time to issue the SMM. (An SMM used to express a benefit enhancement or neutral SPD change does not have to be issued until 210 days following the end of the plan year.)

- Insurance carrier approval — Employers holding insured coverage must first obtain carrier approval for the proposed change and then incorporate the change in its insurance contract. Depending on specific policy terms, such a change might have undesirable premium implications. For a self-funded plan, the third party administrator would need to have its systems set up to accommodate this change.

- Medical trend — Within the framework of HIPAA safeguards, self-funded plan sponsors will want to closely examine the particular dynamics of their plan population to maximize the opportunity to help improve overall medical trend factors. Specifically, what financial advantages could be derived from the plan sponsor agreeing to absorb new chronic condition coverage costs? Arguably, absorbing such costs should mitigate larger plan expenses — but any meaningfully thoughtful analysis to make optimal design choice decision will likely require some reasonable time investment. (As a general matter, insured employers would not hold access to the PHI used to run such analysis.)

Although plan sponsors have sought this type of flexibility for years, implementation requires a series of time-sensitive action steps.