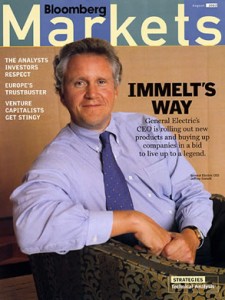

If you work for General Electric and Jeff Immelt asks you to meet with a customer and explain a GE product, you will be inclined to say yes because he is the CEO.

You might also like him, or find him inspirational, or agree with what he wants. You might consider his request part of your job. But what is likely to be most influential with you is that he is the big boss in GE, and as the big boss he has the legitimate right to ask you to meet with this customer.

Because of his role, Jeff Immelt has tremendous power at GE.

Role power exists because people live and work in social organizations, and for those organizations to function, the people in them have to play various roles (e.g., mother, father, teacher, principal, president, vice president, priest, rabbi, committee chairperson, fire chief, sergeant at arms, senior editor, electrical engineer, strategic account manager, human resources director, and so on).

Role power operates within a domain

Implicit in those roles are expectations and agreements about the role’s task responsibilities, span of control, decision authority, and relation to other roles. Sometimes, to ensure that everyone knows what he is supposed to do, those expectations and agreements are explicitly negotiated and codified.

If the roles are formally defined, they represent the legitimate authority granted to the people playing those roles. Even when roles are not formally defined or when power is shared among group members, people act as though the roles various members are playing have legitimate authority.

Role power operates within a domain, and its power typically does not extend beyond that domain. A regional customer service manager for an appliance company, for instance, has role power within the scope of her responsibilities and her region, but she has little role power outside her region and no role power at home, at least not as a manager (although she may have power in her role as a partner, spouse, head of the household, or mother).

Some roles, however, have a halo effect because of their significance. I am not a Buddhist or a Tibetan, but if I met the Dalai Lama I would show him deference (and probably allow myself to be influenced by him in ways acceptable to me) because of his character power, his reputation, and his role as one of the world’s great religious leaders.

On the other hand, if I met the managing director of a European company I don’t work for, and he ordered me to open a branch office in Hong Kong, he would be trying to exercise influence well outside his role domain, and I would think he’d lost his mind.

“One of the strongest sources of power a person can have”

Under most circumstances, role power is one of the strongest sources of power a person can have. Its strength comes from our tendency to conform to the social norms of the groups we belong to and therefore to accept a leader’s legitimate right to tell, ask, lead, or influence us to do what he wants. We are inclined to comply if what the leader wants or demands is within the scope of his authority.

If I am an assistant professor in a university, for instance, I understand that my department chair has certain powers by virtue of that position. The dean of the college I belong to has certain other powers (greater than my department chair’s powers). The academic vice president of the college has even greater powers. And so on. Because I understand and implicitly accept the hierarchical system in which I am working, I expect the people in these roles to try to influence me in particular ways, and I will be inclined to go along with their leadership and influence attempts if I deem them legitimate.

However, human beings are not sheep, and most of us don’t willingly submit to authority without feeling some tension between our urge to conform to the social norms of our culture and organization and our need for autonomy and freedom. Most Americans don’t like to be told what to do (and I suspect this applies to most people in the world).

Our impulse to express our autonomy begins in childhood as we develop an independent sense of ourselves and start to rebel against parental authority. As adults, most people come to accept the hierarchical structure that is part of nearly all organizations, so they grant people with role authority the right to make demands or requests of others. Still, because of the tension between the urge to conform and the need for autonomy, when role power is used to lead or influence people, the outcome is more likely to be compliance rather than commitment.

In organizations, people may accept what someone with legitimate role power wants them to do, but they rarely embrace it, and this is particularly true in professional services firms.

As a group, professionals tend to be independent and self-directed. The leader of a group of professionals may have legitimate role power, but if he exercises it too forcefully he is likely to engender passive resistance or even open rebellion as many of the professionals he is leading react to his clumsy attempts to control them. Many professionals consider themselves equal to the person designated as the leader, and governance or oversight committees may circumscribe the leader’s power and disperse some of that role power to others in the organization.

Coercive power, reward power, legitimate power

In their study of the uses of social power, John French Jr. and Bertram Raven identified three sources that are relevant to organizational roles: coercive power, reward power, and legitimate power.

Coercive power is the power to punish — to create consequences for those who do not comply with what you want (i.e., conform to your demands or respond to your requests). The opposite is reward power — the ability to create favorable consequences (or remove negative ones) for those who do comply.

Legitimate power is the perception that a person in a particular role has the right to prescribe behavior or make demands upon others who fall within the scope of that role’s authority. A company president, for instance, can reward employees in the company by increasing their compensation, promoting them, awarding bonuses, giving them premier assignments, involving them in exclusive events, or recognizing them publicly. The president can punish them by firing them, withholding favors, reducing their responsibilities, shunning them (e.g., disinviting them to exclusive events), or chastising them publicly.

The president’s role gives her the legitimate power to issue orders, control activities and people in the company, and make demands and requests, which people are likely to comply with because they came from someone with the legitimate authority to make them and because that person has the power to reward or punish. French and Raven defined these as separate sources of power, but they are inherently part of any legitimate role in any organization, so I consider them all part of role power.

The capacity to reward or punish others in an organization (which could be a family, a business unit, a company, or a nation) makes role the strongest power source of them all. Consequently, role power is the source most likely to be abused. In the hands of an unscrupulous leader, role power has the capacity to inflict an extraordinary amount of damage.

Abuses of power: In business, the exception rather than the rule

To understand how overwhelming role power can be, we have only to consider Hitler, Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Idi Amin, Kim Il Sung, and Robert Mugabe — despots whose megalomaniacal rule proves that in the iron grasp of a dictator, backed by the coercive power of the police and the military, role power is stronger by many orders of magnitude than any other power source.

History has repeatedly shown how difficult it is to effectively moderate that power once it has been granted unless a strong system of checks and balances is in place — and even then, determined autocrats have circumvented those checks and exercised power far beyond the legal authority they actually possess.

Fortunately, in business, such abuses of power are the exception rather than the rule.

In most organizations, checks and balances exist that either inhibit leaders from abusing their role power or prevent abuses from continuing for very long. The majority of business leaders follow their own moral compass in exercising their role power.

The best of them do not use their role power heavy-handedly because they understand that the most effective way to motivate others and build a healthy organization is to inspire and delegate rather than to command and control people.

Excerpted from The Elements of Power: Lessons on Leadership and Influence by Terry Bacon. Copyright © 2011 Terry R. Bacon. Published by AMACOM Books, a division of American Management Association, New York, NY. Used with permission. All rights reserved. http://www.amacombooks.org