Last week, a spat about the veracity of government data between a prominent HR academic and the Bureau of Labor and made unexpected news.

According to Fortune magazine, latest US Bureau of Labor Statistics data found there had been a sharp decline in the number of companies allowing staff to work from home. It revealed 72% of employers polled said their employees worked remotely ‘rarely’ or ‘not at all’ last year – up from 60.1% in 2021 – suggesting, it said that mass WFT is now ‘dead’.

Well, in not so many words, ‘tosh’ was the response from Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford economics professor and cofounder of the Working From Home Research Project (WFHP).

For those who haven’t heard of it, the WFHP team surveys 5,000+ US working age adults and 1,000+ firms each and every month, asking them precisely about at-work, hybrid or remote working practices.

Bloom’s big beef is that the question being asked by the BLS is misleading, and it causes companies to report that no teleworking exists with them when he says it clearly does.

Why it matters to know

OK, there will no doubt be many who say this is a storm in a tea up. But is it?

While disagreements between scholars and government are nothing new, this brouhaha here is arguably about more than simply a squabble over data.

Because what’s really being argued about is what exactly ‘is’ the true WFH rate?

It is important to know, because for those organizations that are still grappling with the concept of returning staff to the office, many are desperate for accurate data to determine what their response should be.

They want to know how they should respond to employee requests for WFH; and what they now consider to be normal, or not normal as part of their reaction to it.

In short, it matters to know where things currently stand, so that policy can be planned going forward – including (most controversially), whether HRDs decide it’s time to mandate returning to the office.

To put it mildly, employers want to know that they’re not doing anything out of the ordinary.

Is there a definitive WFH statistic?

According to Bloom, in 2019, only about 5% of full-time work was done from home.

This share obviously ballooned dramatically the following year, to more than 60% in April and May 2020, in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

His suggestion is that this share – which has steadily declined to 27% – will settle to about 25% this year.

This data sort-of chimes with US office occupancy rates, which have recently reached 40-60%, and average 50% occupancy.

The problem though, is that there is a still a level of conjecture. And where there isn’t clarity, it will most likely only intensify the sense of entitlement that each ‘camp’ [‘working working’ versus remote working’] feels they have.

The spectre of forced returns

Lack of clear data around what is now acceptable is already leading, say some, to employers hardening their stance on working remotely, and deciding for themselves to mark their own mark in the sand.

Several high-profile firms are now rowing back on previous WFT pledges, and mandating working from the office.

These include Amazon (mandating a minimum of three days per week in the office from May 1st this year); Apple; Citigroup (a minimum of two days a week); Disney (four days a week in the office); Goldman Sachs (every day); Google (three days); and JP Morgan (half to come back five days a week and another 40% to come in a few days a week).

In a dramatic U-turn from its previous ‘work from anywhere’ policy, Salesforce now wants ‘non-remote employees’ to work in the office for three days a week, while for those in “non-remote” and “customer-facing” roles, it’s four days a week that’s being demanded.

So what is the ‘new normal’?

For HRDs trying to determine what their ‘new normal’ should be, reports of high remote working at one end of the extreme and compelled office working at the other does not make things terribly easy to make a judgement call about.

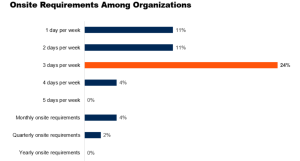

Fortunately, Gartner is attempting to help. It recently (January) published its own data on some of the return to office requirements being pursued by employers.

What it research clearly shows (see above), is that a middle-ground of working three days per week seems to be the overwhelming compromise currently being pursued.

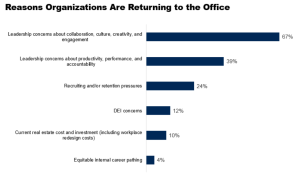

Their top reasons for requiring this minimum level of in-office working were also pretty clear (see below).

The big worry is that leaders fear a loss of collaboration, and creativity, which in turn impacts culture and engagement (67%). This is nearly double fears about productivity.

The productivity debate around working from home appears to have been won – it’s just that now it’s been replaced by softer impacts to company culture.

What do HRDs need to do if they want their staff to return?

On paper, getting a feel for what typical WFH rates actually are should give HRDs the ammunition they need to communicate that working in the office is now not only their ‘preferred’ modus operandi, but it’s also the ‘normal’ one, and that if employees have big objections to it, then they are out of kilter with the real post-pandemic.

That’s the theory of course!

For there’s plenty of data that also suggests a good proportion of workers (39%, according to a survey of 2,300 workers from Owl Labs and Global Workplace Analytics), would quit if their ability to work from home was taken away.

The same poll also found nearly half would stop working as hard if the benefit was eliminated.

Gartner, too, observes that there are barriers.

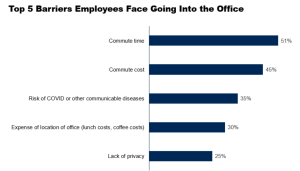

Most employees it polled (51%), now regard the commute as their top reason to prefer working from home/ This is followed by commuting costs (45%), and interestingly, a sense that the office gives them a distinct lack of privacy (25%) – see below:

Things staff ‘would’ go back for (and don’t forget incentives)

On the plus side, there are still many reasons employers ‘would’ consider working in the office for – everything from building relationships with their colleagues and managers (38%) to collaborating with others more generally (37%), and – again, interesting – being visible (19%).

Gartner’s advice is to big up the reasons they would return.

But crucially it also urges HRDs to consider using incentives to wean staff back too.

Some 60% of organizations polled by Gartner admitted that their employees didn’t want to come to the office because they saw no compelling reason to be there.

It argues this needs to change, but currently finds 32% of companies offer no inducements of any kind to get employees to come back to the office.

It suggests that those who do – however – get more buy-in, and inculcate less of the ‘stick’ and more of the ‘carrot’ approach.

HRDs need to experiment, suggests Gartner, so that they get in-tune with what would work for their staff.

Overall, it found that only 10% of staff would choose to come to the office for organizational perks like free food, while only 11% would choose to come for better broadband and other services.

More (25%) would return to the office for better equipment, tools or supplies that are only available on-site. Most would be motivated to go to the office for social incentives, including collaborating with others to build relationships.

Amongst the more popular incentives used were company-sponsored events at the office (44%); company-sponsored meals at the workplace (32%), offering flexible hours to avoid peak time commute traffic (26%) and improving workplace spaces (24%).

Articulate the ‘why’

Gartner is clear in its recommendations: “Many organizations want employees back in the office. However, they may find it difficult to obtain buy-in from employees for arbitrary requirements, such as to work x number of days in office per week, if they do not communicate a clear rationale for doing so,” it says.

Having a handle about office working normalcy rates, and what is now the evolved accepted ‘norm’ help those who face resistance from staff.

Gartner concludes: “While HR leaders may be eager to get employees back to the workplace, they should ensure their return-to-office strategies have a clearly defined, valid purpose.”

STATS: What would make staff return to the office?

In separate research, at the end of last year Clarity Capital surveyed more than 1,000 workers to find out what would make them return to the office.

Here are the results:

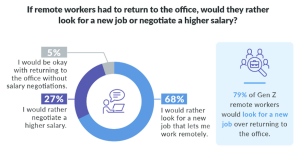

- 68% said they would actually look for a new job if they were told to return to the office.

- That said, only 5% would be totally ‘unwilling’ to negotiate returning to the office. Some 45% would be ‘somewhat’ willing to negotiate their return, and 50% said they would be ‘very willing’ to negotiate their return.

- In terms of what it would take to lure them back, most said being given flexible work hours in return (34%), followed by their own office space (33%), a casual code (32%) and a four day week (30%).