It’s nearly three years-on since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, but the debate about where staff are most productive only seems seems to be getting more and more divisive.

Recently Stephen Schwarzman, chief executive of New York-based private equity firm, Blackstone, joined a growing list of CEOs who have had enough of home working.

He waded into the debate, categorically claiming that staff still dressed in their PJs did not work as hard as than those who’d gotten up hours earlier and braved the stress and the strain of a commute before even switching their PCs on.

So who’s right though?

The ‘productivity problem’

The problem with productivity is that it’s a complex concept to measure.

When surveys ask remote-working staff if they’re more productive, the responses they seek are typically ‘self-reported’ metrics. As such, when staff say they feel more productive, it’s a judgement call more than anything else. Research shows the conclusions staff reach about their productivity are partly due to them not including commuting as part of their work day [managers meanwhile, tend to ignore commuting time], or because they don’t feel as stressed working from home as they do in the office.

The trouble is, being less stressed doesn’t always correlate with more output.

Take, for instance, recent research by two Harvard doctoral students into call center workers employed by a big online retailer, pre- and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The students found the average office-bound worker answered 26 calls a day – that’s around one call every 20 minutes. Those working from home however, spent an extra 40 seconds on each call – making them mathematically 12% less productive. The inference is clearly that, in this instance, staff feeling relaxed is a precursor cause of reduced productivity.

What we don’t know is whether each longer call improved what the contact center world calls ‘first-time resolution’ rates. Dealing with calls better, first-time, can actually boost productivity by not requiring follow-up calls. But the example is just one scenario where HR professionals can get themselves into all sorts of knots around the statistics around productivity.

Here’s another example: An October 2022 Future Forum report claimed workers with fully flexibility schedules reported 29% higher productivity and 53% greater ability to focus compared to those not on the same terms.

Countering this came data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, which found productivity dropped 7.4% in the first quarter of 2022 and 4.6% in the second quarter (when WFH was at its peak).

The biggest ‘bomb’ though, supposedly came over the summer, when a paper from WFH Research. WFH Research is led by professors Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis (all long-term proponents of WFH), but their paper seemed to blow their whole argument out of the water. A working paper, published by Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy and Research, found fully remote work is associated with 10% to 20% lower productivity than fully in-person work.

For what it’s worth, the professors sought to explain the drop, by emphasizing that communication issues prevent remote workers from being fully productive, but it illustrates the extent to which people will often make of the stats what they want them to say.

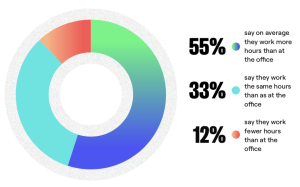

And let’s not forget that there’s something else complicating matters further: the tendency for remote workers to actually work more hours – which doesn’t make calculating productivity any easier.

For instance, if staff are dong the same amount of work (output), but simply spreading it over a longer period, then that’s them theoretically being less productive.

But, even if they still getting a bit more done per day, while they might look like they’re being more productive on a ‘per day’ basis, they’re actually being less productive on a ‘per hour’ basis.”

See what I mean. It’s complicated!

For employers on the ground, this is stuff they are all grappling with – so what are they making of it?

To hear one boss’s thoughts on the matter, TLNT recently spoke to Bjorn Reynolds, CEO of Safeguard Global, a global workforce management company.

He didn’t pull his punches when he said he felt staff working remotely definitely get more done:

Q: Bjorn, you believe productivity is not going to increase when companies force employers back to the office. Can you explain your thinking?

A: “To me, it’s pretty simple. The in-office ‘productivity boom’ is a fallacy. It’s a shot in the dark. All executives who think productivity will rise are failing to consider what their employees actually ‘want’ to do. There just isn’t a groundswell of people saying ‘I want to come back to the office,’ and so my take is that when you force people to come back, that’s not going to make them psychologically in a better place to improve productivity.”

Q: But how do you square this with data that suggests the opposite – that remote staff are less productive?

“I think it’s hard to say that productivity always drops across the board, because you only have to look at things practically to say if someone is spending an hour commuting twice a day, that can’t be good. When executives are trying to drag people back to the office, I believe they’re looking at their business performance figures, and they’re blaming them only on the things that they can see – ie not having their people around them – rather than acknowledging more deep-rooted changes to the business landscape.”

Q: So what do you think the real reason is for getting people back to offices?

A: “On the one hand, I have a big suspicion that back to work mandates are just being used to disguise making layoffs – by making people choose to quit themselves. But on the other, I do just feel the whole ‘back-to-the-office’ thing is just not being thought through. I think that what executives are really moaning about is perhaps that people are not able to collaborate as much – but that’s not productivity as such. Sure, when you get people back, you get people in front of each other in an office – but does that really turn into extra productivity? Or is people being able to choose how and when they work more likely to encourage them to go the extra mile? I know what I’d pin my beliefs on. We surveyed our own staff, and only 2% said they wanted to permanently work in an office. Most – 70% – wanted to remote in some form of hybrid/remote way.”

Q: Do you know if you own people are more productive working remotely, and how do you know your people aren’t just working more hours?

A: I struggle with any company that says they don’t know if they’re people are more productive or not in the office or not. For me, our staff not being in the office far outweighs being in one – because they are excited to work for us, and they don’t want to leave. We trust our people to work their schedules, and we ensure they’re hitting metrics. We have data around what people should be doing, and if they’re starting to fall behind, we would try and work out why, just like if they would if they were in an office. I think if people want to work in the evening because of a family matter in the day, that’s fine. You’ve just got to give people the right frameworks. We accept that being in the office isn’t what creates graft. It’s the projects people are on that do this. We measure, and we know if anyone is starting to fall behind.

Q: Do you measure your people ‘more’ now they’re remote?

A: “Not especially. It’s a balance. We say we’re here to support rather than to monitor. If there are elements people miss about being in the office, we offer hybrid work, so they can get to see people they work with.”

Q: So productivity: up or down when people are remote?

A: “For us, it’s up. Our retention levels are 90% at the moment – and for me, that’s one of the biggest productivity gains alone. When people stay, they know more coding; when they know more coding, they get more done, and they get more done, quicker. We, as employers, now have to ask how employees want to be engaged now. That’s what is needed to win in business now.”

What the data says:

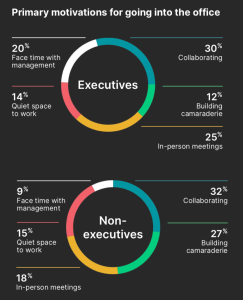

According to the Future Forum, collaborating is the number one reason motivating non-executives to go into the office (32%), followed closely by building camaraderie (27%). Executives, too, prioritize collaboration as their top motivator for in-office.

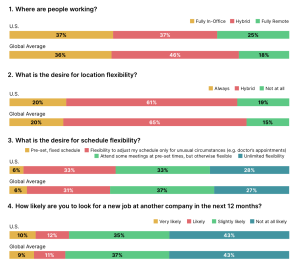

In the US fewer employees are working either fully remote or hybrid, compared with the global average:

According to research by Owl Labs most remote workers work longer hours: