Hear the phrase ‘toxic workplace’ and it’s entirely likely most HRDs will immediately start to wonder what cultural issues are afoot.

Few (if any) would straight away consider it in relation to what the word toxic means – as in containing actual toxins that could be harmful to people’s health.

Well maybe it’s time HRDs started to think about toxic workplaces in this very different light – especially as the back-to-office march rumbles on.

For the fact of the matter is, offices are not always the cleanest or healthiest places to be in when it comes to air quality. And a growing body of scientific evidence is showing poor air quality is increasingly linked to poor cognitive ability, lower productivity, the susceptibility to ill-health and general lethargy.

Here’s why

It’s already been established that as well as having high levels of particulate matter (or particle pollution), poorly ventilated offices can be hotspots for what’s also know as ‘stagnant air’ – which features higher levels of CO2.

Humidity levels outside the traditionally good 40-60% range could also create the right conditions for pores, viruses, bacteria and other toxins, while all buildings exhibit some degree of Volatile Organic Compounds (or VOCs).

More recently however, science is now making the link between this poor air quality and its impact on employees.

One of the strongest pieces of research comes from the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health – which in 2021 found there is a strong causal link between office air quality and employee cognition and productivity.

It studied offices for more than a year in six different countries, and found that increased concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and lower ventilation rates (measured using carbon dioxide (CO2) levels as a proxy), were associated with slower response times and reduced accuracy on a series of cognitive tests.

The researchers noted that they observed impaired cognitive function at concentrations of PM2.5 and CO2 that are common within indoor environments.

Why it’s time to think about the air your employees breathe

According to Serene Almomen, CEO of air quality management company, Attune, this data should be a wake up call to any HRD serious about the health of their in-office employees.

Speaking to TLNT she says: “Covid brought attention to the fact that the air we breathe make a difference to our health. While awareness was predominantly around the transmission of the Covid-19 virus, it has nevertheless put the spotlight on air and the impact it has.”

She adds: “Typically, most HRDs have only tended to be concerned about air temperature, and whether offices are too hot or cold. But now they need to shift their attention to air flow, C02 and airborne risks from things like particulates.”

Staff notice when buildings don’t feel right

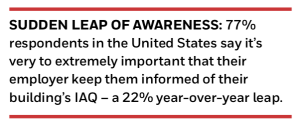

If HRDs aren’t thinking about this, they arguably should, because for employees themselves, data suggests this is a rising concern.

As well as polling that shows staff are still reticent about returning to the office because of Covid-19 risks, data from the recently published third annual Healthy Buildings Survey by Honeywell reveals additional concern about overall office air quality.

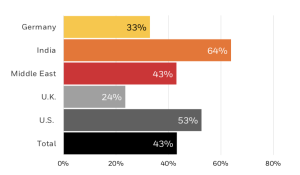

It found that nearly half (43%) of surveyed office workers are “very or extremely worried” about their building’s indoor air quality (IAQ).

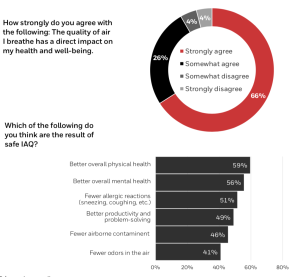

It also found that 97% believe good IAQ contributes positively to their productivity, and (perhaps significantly), it revealed that more than one in five surveyed employees (21%) said they would look for another job if their employer didn’t adopt measures to maintain a healthy indoor environment.

All told, 95% of American workers said their expectations about in-office air quality had increased over the past three years.

Almomen says: “High levels of C02 in a building can impact mental functions, but also increase people’s susceptibility to illness.”

She adds: “It definitely the case that more awareness in this area is needed. Most buildings don’t have particulate matter monitors, and they don’t measure their air quality. Even simple interventions – such as opening windows – may not improve things either, as it will simply let bad air in from the outside, especially if an office is in a highly build up area, or above, for instance a metro.”

Still not convinced?

Aaron Altscher, is director of technology Initiatives at Carr Properties – which provides serviced office properties to hundreds of employers. It’s recently partnered with Attune to create monitoring in all its buildings.

Altscher says: “Air quality has been hugely relevant for people as they return to the office, and now they want to know that if they are in an office building, they will feel refreshed and alert and able to work without getting ill.”

He adds: “We’ve recently rolled out indoor air quality and atmospheric filtering in all our locations, to try and make offering a healthy work space a core pillar. It’s not always easy to do, and it needs doing on a floor-by-floor basis, but we look at where air gets drawn from and what the relative CO2 and VOC levels are.”

According to Altscher, CO2 levels can change significantly according to different levels of office occupancy. He says monitoring the air helps him determine whether an office is at ‘over-capacity’ from an air quality point of view.

“I can see us writing rules about how offices air changes according to peak use (typically Tuesdays-Thursdays now), compared to less busy times,” he says.

He adds: “When air quality is good, people don’t tend to think about it, but when it is bad, people do sense it, and I would say it’s now incumbent for HRDs to really look at it, and how it impacts their people.”

What the data says…

Honeywell’s ‘Workplace Environmental Impact’ report, 2023 reveals in-office air quality is now a major concern:

Percentage of workers worried about the Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) of their office