You don’t need to be politically current to know that immigration has been one of the hottest topics in recent years.

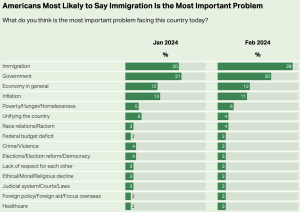

In the most recent Gallup poll it was chosen as the #1 problem facing the US:

The vast numbers of people attempting to enter the US from the border with Mexico have created a crisis.

Depending on which political party you listen to, the mess at the border is either the result of a desire to have open borders, or by people escaping poverty, violence, and persecution in their home countries.

There’s some truth to both these claims, but the overarching reason is simple economics: supply is trying to catch up with demand.

As any first-year economics student knows, when there is an imbalance between supply and demand for anything, pressure builds for either one or both to change until equilibrium is reached. And the imbalance is largely the result of an immigration policy that is outdated and disconnected from reality.

The US economy is highly advanced, and the spotlight is on things like AI, self-driving cars, humanoid robots, and VR. But despite the visions (or fantasies), of a tech delivered nirvana soon to come, the fact remains that we still need huge numbers of low-skilled workers.

Entire sectors of the economy and industries would collapse if not supplied with migrant labor. That includes agriculture, meatpacking, construction, cleaning, child and eldercare, hospitality, warehousing, distribution and transport.

These industries collectively employ around 57 million workers, but the staggering fact is that, currently, they also have more than 6 million job openings.

No technological advances are even remotely close to being able to reduce the demand for labor in these industries in the foreseeable future.

An aging population

Demand for people, however, is only going to increase.

Our population is aging and living longer. It needs more food, more housing, and more care.

The US population is projected to increase from 336 million in 2023 to 373 million by 2053. As growth of the population aged 65 or older outpaces growth of younger age groups, the population curve will continue to become older.

In fact, the ratio of people that are 65 or older to the prime working age people (those aged 25-54 years), is projected to increase from 34 to 46 people per 100 prime-age people in the next 20 years. Life expectancy is expected to increase from the current 78 to 85 years over the same period.

With natural population growth projected to slow (averaging 0.3% per year over the next 30 years), all remaining growth will be driven by immigration as fertility rates remain below the rate that would be required for a generation to exactly replace itself in the absence of immigration.

The US passed the point of no return in 2008 when the fertility rate dropped below the replacement level (2.1 per woman). It now stands at 1.64 and the trend is downwards.

The labor force of prime working age is estimated to grow at an average annual rate of just 0.2% over the next 30 years. That’s a sharp decline from the recent past. Compare that to the past 40 years when the population grew at a rate of 1.1%, and the prime working-age population grew at a rate of 0.9%.

An aging population that lives longer needs care providers. There’s been a sharp rise in employees functioning as unpaid family caregivers, in addition to working full time. It’s estimated there are 53 million adults who care for a spouse, elderly parent or relative, or special-needs child. That’s up from 43.5 million in 2015, and includes caregivers who also work full-time jobs.

Almost a quarter (22%) of individuals must split their time between full-time work and care giving duties. These duties often include medical and nursing tasks. These people are essentially working two jobs.

The amount of time that caregivers spend care giving has also been increasing. In 2020, caregivers spent an average of 9 hours per week providing care. In 2023, that increased to 26 hours per week. Almost half spend 10-29 hours of their week devoted to caregiving. A significant quarter spend 30 hours a week (or more), providing care.

The majority (61%) of US households are dependent on two incomes to remain financially stable, so the increasing demand for family members to stand in as family caregivers has serious economic impact. The direct cost of caregiving on the US economy is nearly $44 billion, given the loss of more than 650,000 jobs. The impact would be even higher if migrant labor is not available.

Migrant labor

Migrants do a lot of critical jobs that few others are willing to do.

They work in industries that include millions of “dirty jobs” that few aspire to.

The work is hard and the pay is low. The majority of migrants work in jobs that pay less than $42K annually. In a famous example of the reality of the need for migrant labor, when the late Senator John McCain was running for president, he was confronted by a mob of protestors opposed to his plans for immigration reform. The senator told them: “I’ll offer anybody here $50 an hour if you’ll go pick lettuce in Yuma … and pick for the whole season. So, OK, sign up!” There were no takers.

Immigration also bolsters the labor force.

Migrants tend to be of working age and reduce the dependency ratio and slow population aging.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows that foreign-born workers, particularly men, participate in the workforce at a considerably higher rate than their native-born counterparts.

In June 2023, the total labor force participation rates for foreign and native workers were 67.0% and 62.1%, respectively; for men only, these numbers were 77.9% and 66.7%, respectively.

Research has also shown that immigrant labor creates more employment opportunities for natives.

This counters the “lump of labor fallacy,” or the false idea that increased immigration must always come at a cost to domestic employment.

Immigrants often take lower-skilled positions not commonly held by native-born workers. Immigration also provides vital financial support for an aging population.

The graying of America necessitates significant spending on Social Security, Medicare, and other federal programs, while leaving the country with a smaller share of workers to pay taxes to support these programs.

Reform the system

Unfortunately, we are at an impasse on immigration reform.

Neither party is willing to acknowledge what they know to be true.

The best solution would be to make it easier for migrant labor to come and go.

Such a system – the Bracero program, existed from 1942-1964.

It was designed to fill agriculture shortages during World War II and offered employment contracts to 5 million workers annually.

It would also significantly reduce the incentive for migrant workers to stay in the US illegally, as is the case now when a migrant has no guarantee of being able to get back to a job after returning to their home country.

But given that migrant labor is seen as a threat to the country there’s little possibility of change.

So is there light at the end of the tunnel? One can always dream.