Do your managers set up your employees for the “Thrill of Victory” or the “Agony of Defeat?”

If you don’t remember the commercial those phrases come from — and the image of the poor skier tumbling down the slope, personifying The Agony of Defeat — I’ll ask the question in a more standard way:

Do your managers do everything possible to enable and empower employees to succeed, or do they let busyness and carelessness prevent employees from getting the information, clarity, and resources they need to succeed?

It’s easy to get this wrong in today’s world

To be honest, I still occasionally catch myself falling short in this area. At times, I let my busyness translate into not wanting to take the time to explain my expectations as thoroughly as I should, or be as generous with my time to answer in-depth questions from a subcontractor who sincerely wants to do a great job. When I catch myself doing this, I remind myself how frustrated I feel when I am on the other side of that dynamic.

Think of how frustrating it is to have someone ask you to do work, and expect it to be great — as they should — but then not do their part to make that possible.

A common example in my work is being asked to speak at an event and then having key stakeholders unwilling to take the time to answer questions or be interviewed, or my main contact person not responding to requests for information that would help me provide them with the best, most useful program.

Because of their busyness and carelessness, they don’t give me the information that could help me provide them with as much value as I could potentially provide.

When this happens, I find myself thinking:

I bet this is what it’s like for employees in this organization. I bet they are continually thwarted in their efforts to do their best work. I imagine their desire to make a difference, to go above and beyond, and to come up with new ideas, has been drained out of them over the years by this kind of non-responsiveness and carelessness.

What happens when leaders get this right?

In contrast to this all-too-common occurrence, here’s an example of a leader doing his part to set others up for success. This example will give you a clear picture of leader behaviors that enable and empower employees to do great work.

These behaviors also foster a resilient, “We can do this” attitude because employees get to feel the thrill of victory rather than the enervating effect of feeling impotent and ineffective due to being constantly hamstrung by an unresponsive boss or leadership team.

Doing the things I will share below also fosters passionate engagement, because nothing fosters enthusiasm for one’s work more than the feeling of self-efficacy and accomplishment.

So here’s what happened:

I was asked to speak at a quarterly leadership conference for a large healthcare system on how to foster a resilient “can do” spirit in employees who were facing a major technology roll-out.

My primary contact in this engagement was Ben, the senior manager of the organization’s center for leadership and development.

Even though our roles were as collaborators vs. a direct report/supervisor relationship, the qualities they demonstrated, and the principles extracted from them, apply to any situation where a leader is delegating or enlisting the involvement of others in the creation and execution of an initiative.

How to enable and empower success

In my conversations with Ben, I was struck by several refreshing characteristics of the way he communicated. The following are key takeaways based on those characteristics:

Demonstrate sincere enthusiasm for the project and the difference it can make — Enthusiasm is contagious. If you want your followers to be enthusiastic, make sure you express yours.

While I am ordinarily enthusiastic about my work, Ben’s enthusiasm dialed mine up to an even higher level. As I listened to the enthusiasm in Ben’s voice, I found myself thinking, “This is going to be a very cool event and I’m excited to be part of it.

When you lead projects or communicate your vision to your team, are you “all business” or do you let your enthusiasm show. Don’t be shy or staid about communicating what’s great about your project or new initiative. Let your passion shine through. It will be contagious.

Communicate genuine confidence in their ability to do a great job — Great leaders don’t just show enthusiasm for the vision, they show enthusiasm for the people helping to make the vision possible. They communicate, “You can do this,” “I have faith in you,” and “You’ll be great at this.” Whether through direct explanation why they believe this, or by the totality of their communication, they demonstrate that their stated confidence is grounded in an understanding of you, your work, and your ability.

Ben did this on several occasions. When he would discuss his vision for the event and the desired outcomes, including what was most important for me to accomplish, he would say “I know you’re going to do great” on multiple occasions.

He didn’t do what some people do in an attempt to be motivational, which is just say, “Oh, you’ll be great” with no indication of what they base that statement on. When such “encouragement” is unaccompanied by an understanding of the other person’s work or ability, it simply comes off as an insincere, superficial, and sophomoric attempt at being motivational.

Rather than this meaningless approach to encouragement, Ben demonstrated in our conversations that he was familiar with my work and expertise. So when he did express confidence that I would do a great job, it came across as sincere and grounded in understanding.

Because of that, it was meaningful and appreciated.

Communicate the “After Picture” and “Line of Sight” with clarity — Ben was crystal clear in communicating the conference’s objectives and the role my two presentations would play in helping them achieve those objectives. He did what is so important at both the managerial and leadership level: He provided both a clear target and specific line of sight between a contributor’s role and the target.

When you communicate a clear vision, a clear “after picture,” you give people a sense of control rather than the sense of impotence and futility one gets when one isn’t sure what the goal is and what they’re supposed to do to make that a reality.

Think about times you’ve been on the receiving end of an ambiguous directive, where you were not really sure what the end goal looked like, what success would look like, and what outcomes the project or initiative were meant to accomplish. Think of how much less confident you were on how to proceed and whether you would be successful, without a clear picture. Clarity instills confidence and inspires eagerness.

Because I knew precisely what they wanted to accomplish, I knew what I needed to do to make that happen. I felt set up for success.

Balance clarity and commitment to the vision, with an openness to input and alternative points of view — This dynamic in our conversations was especially fascinating to me because it demonstrated an artful interplay between two disparate, yet important goals when communicating your vision or when delegating a project.

On one hand, you want to be enthusiastic about your idea, your project, or your vision. You want to communicate clearly what it looks like. Also, if you have clear ideas and opinions, you want to communicate them clearly and confidently.

Conversely, you don’t want to come across as so convinced of the rightness of what you say, that the other person might be reluctant to challenge you and offer different, and potentially better, perspectives and approaches.

I was struck by how Ben would often say things like, “So, that’s what I’m thinking would make sense. What are your thoughts?” and even encouraging counter points of view by saying something like, “That’s what I’m thinking, but maybe I’m off base. Maybe there’s a better way your topic could fit into this theme. What are your thoughts?”

Note how that explicit message of, “I want you to challenge me. I want you to speak up,” makes it far more comfortable for the other person to bring up their point of view than if your voice tone and word choice say, “My perspective is the correct perspective.”

If the person in a leadership position presents their point of view in a “case closed” kind of way, unless an employee is extremely assertive and rather fearless, they will not give voice to their concerns or alternative perspectives.

And because of that, leadership misses out on input that could make a critical difference in the success of their initiative.

Provide as much context and information as requested, and make it clear that doing so is not a problem — Despite his significant work demands, he was unfailingly gracious in making it clear that whatever I needed in terms of context, backstory, and access to other leaders he would make happen.

I was both appreciative of, and impressed with, this attitude. It made it easy and comfortable for me to ask for what I needed, rather than have to perform the unpleasant cost/benefit analysis of computing the added value I would be able to provide with more context, and compare it with the potential friction my putting extra demands on his time might create.

Think of projects you’ve been assigned that required you to get significant context, and the leader from whom you needed to get that context made it clear through their words and voice tone that you were an imposition when you attempted to do so. It doesn’t take too many of those experiences to opt for the “I won’t ask anymore, because it’s just annoying them” choice versus the “I will ask for what I need so I can provide the most value” choice.

Reinforce the message: “Don’t be shy about asking for what you need” — Expanding on the last point, Ben made it clear he wanted to give me as much help and support as possible. He frequently included, “Don’t hesitate to call if you have any questions” in our conversations.

Doing this is one of the most important things a leader can do to set their people up for victory, rather than defeat, or having to do less than their best work because they didn’t get the information, direction, tools, or resources they needed.

Clearly communicating, “Don’t be shy about asking for what you need. I’m here for you” also helps prevent learned helplessness.

Learned helplessness can be developed by learning that it’s not OK to ask for what you need to be successful. Getting the message that you’re a bother when you ask for the information and resources you need results in all but the most assertive and tenacious employees learning to make do with less than what they need, resulting in them doing less than their best.

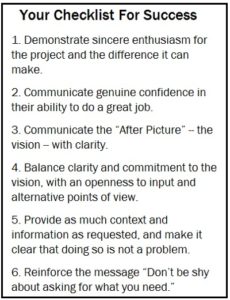

Turn this into a success checklist

In the spirit of Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, copy and paste these six critical practices into a Word document — or click the image and print it out — and give it to all of your managers as a handy checklist to remind them to do each of these, whether they are delegating an assignment or leading a project.

- Demonstrate sincere enthusiasm for the project and the difference it can make.

- Communicate genuine confidence in their ability to do a great job.

- Communicate the “After Picture” — the vision — with clarity.

- Balance clarity and commitment to the vision, with an openness to input and alternative points of view.

- Provide as much context and information as requested, and make it clear that doing so is not a problem.

- Reinforce the message “Don’t be shy about asking for what you need.”