Unless new economic shocks upset the rate of improvement, it will take at least two more years before the U.S. labor market returns to its historic norms.

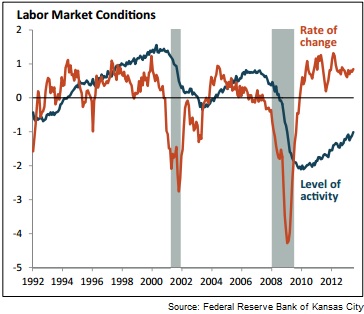

Crunching together 23 different labor market indicators, two economists with the sometimes-contrarian Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City said that though the rate of change is well above the average of the last 20 years, it hasn’t translated into an equivalent rate of improvement in labor market conditions.

What that means is that despite the acceleration in job creation, temp hiring, job availability, and other labor market measures, the national unemployment rate will continue to decline only slowly.

What the economists measure

The indicators developed by the Fed Bank’s economists measure:

- Level of activity: How far are labor market conditions from historical averages?

- Rate of change: How rapidly are conditions changing compared with the past?

Neither is a direct indicator of unemployment or underemployment, though the level of activity takes into both measure — and other measures — into account. As the rate of change accelerates, the level of activity should, which would mean a reduction in unemployment.

Neither is a direct indicator of unemployment or underemployment, though the level of activity takes into both measure — and other measures — into account. As the rate of change accelerates, the level of activity should, which would mean a reduction in unemployment.

Whether the U.S. economy will ever return to the historical unemployment rate of about 5 percent is a subject of much debate among economists. Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco examined unemployment rate changes, saying:

…the “normal” unemployment rate may have risen as much as 1.7 percentage points to about 6.7 percent, although much of this increase is likely to prove temporary. Even with such an increase, sizable labor market slack is expected to persist for years.

No definition of what the new “normal” is

The report from the Kansas City Fed doesn’t talk about what the new “normal” is, or what it will be. Its purpose is to offer a better way of making sense of the monthly economic data that can more resemble a roller coaster than a rocket. Aggregating the various reports, and their often contradictory data, into two measures provides a sharper look at what the data means.

Besides helping economists forecast labor availability and giving recruiters and workforce planners a heads-up about sourcing and hiring, the measures also have implications for Fed policy.

Esther George, president of the Kansas City Fed Bank, has taken a contrarian view of the Fed Board’s bond buying program. She has argued that the market is growing faster than economists think, and for that reason, the Fed should begin cutting back on its aggressive stimulus program and allow interest rates to rise.