Names.

We all have them.

Sometimes they can simply make us laugh out loud [just check out BoredPanda’s recent compilation of funny names, including the likes of Chris P Bacon and Sam Sung].

Sometimes they’re just plain cool (such as having the name ‘James Bond’ – and get this, there are 1,007 of them in America – according to the US Census, which is even cooler).

Sometimes they can carry a certain degree of infamy (there is an estimated 2,767 people called ‘Adolf’ in America, according to MyNameStats.com), while for those who are the son or daughter of an already-famous icon, their name is their passport to things they may not have achieved on merit alone.

But while some regard having a distinctive name or surname as an ice-breaker, and something that gets them noticed (as the 106 Americans called ‘Harry Potter’ will all no-doubt testify to), try telling this to those for whom their name is a source of discomfort or exclusion.

Names create exclusion

Something as simple as a name can a bigger problem than HRDs might think.

Research already shows that those with ethnic-sounding names are already less likely to get job interviews because of recruiter bias towards people with traditional ‘white’ names.

One seminal study by the University of Toronto sent 7,000 fictitious resumes to hiring managers, and peppered with a variety of made-up names.

It found that those which sounded ‘foreign’ stood a far less chance of getting selected for interview – with the research finding English-speaking employers in Montreal, Toronto were 40% more likely to choose to interview a job applicant with an English-sounding name [such as “Jill Wilson” or “John Martin”] than someone with an ethnic name [“Sana Khan” or “Lei Li,”]. This was even if both candidates had identical education, skills and work histories.

Other subsequent studies have found similar results – one showed Chinese people must submit 68% more applications to get an interview; while those with Middle-Eastern names have to submit 64% more.

Mispronunciation

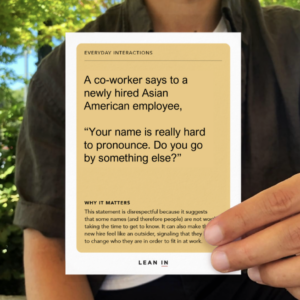

But even when people are ‘in’ work, it’s still the case that those with unusual-sounding or unusually pronounced names feel embarrassed and self-conscious, and worry about whether others can or can’t verbalize their name.

But employers can (and should) play are role here.

And one company – P&G – is doing just this.

As it happens, the month of May is APA Heritage Month – which honors the contributions and culture of Asian-Pacific Americans in the United States. In raising awareness about their rich history and diverse experiences.

P&G is using this awareness month to promote its second ‘The Name’ campaign, which wants to make the point that for people to feel like they belong in an organization, it should start with their name,

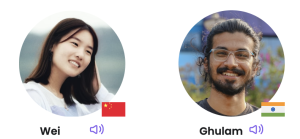

To put its money where its mouth is, P&G has partnered with technology company, NameCoach – which solves mispronunciation issues by allowing companies to embed an audio clip icon next to someone’s name on their list of employees on their corporate website, or include a pronounciation button against existing contacts on a Salesforce database or on their email signatures (see below):

One of the biggest microaggressions that can take place is the repeated mispronunciation of someone’s name,

– Fast company 2020

Although the technology uses AI to accurately create the most likely pronounciation of someone’s name by comparing it to nationality and ethnic data (it will – for example, recognize differences in pronounciation of Henri Martin, an Englishman vs Henri Martin, a Frenchman), staff at P&G can create their own custom pronunciation ‘Namebadge’ clip – which they can then add to their email auto-signature.

P&G is also encouraging staff to share their name pronounciations on social media and other platforms, using the hashtag #OurNamesBelong.

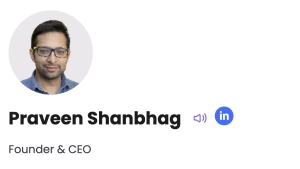

Praveen Shanbhag, CEO NameCoach says: “The correct pronunciation of someone’s name and fosters understanding and respect for the diverse cultures,” and he is not wrong.

Its own study in 2021 found 44% of respondents revealed they had their names mispronounced in an interview, while 41% had their names mispronounced in a customer meeting.

Shockingly, in the same study, 22% of people polled admitted they didn’t introduce someone because they didn’t know how to say their name. Some 16% said they didn’t talk to a coworker out of fear of not knowing how to say their name, and 13% didn’t call on someone in a meeting because they didn’t know how to pronounce their name.

So, perhaps the biggest (and most immediate) difference HRDs can make in their DEI efforts is literally starting with basics – by ensuring staff have any discomfort they experience with names – either saying their own name to a colleagye, or pronouncing someone else’s – completley removed.

If you’re still not convinced, have a watch of this video produced by P&G itself.

Watch this, and you’re guaranteed never to look at people’s names in quite the same way again.

It’s all in the name…

- 19% of Asians say their name makes them feel alienated at work, while 23% admitted it made them feel self-conscious

- 74% of workers say they struggle with how they pronounce colleagues’ names

- 26% of workers say they want to be trained by their employers on using pronouns correctly.

(Source: NameCoach)

- In 2019 Law Firm Slater & Gordon found Black Asian Minority and Ethnic (BAME) workers are either directly or indirectly being told to use more English-sounding names in the workplace. It found three out of five workers felt their career would suffer if they did not Westernize their name. Meanwhile, 34% of the 1,000 BAME workers surveyed saying they had abandoned their birth name on their CV or in the workplace at least once during their career. Of these, nearly half changed their first name, a third changed their family name and a fifth changed both.

- Nottingham Trent University found that when students experienced persistent mispronunciation of their name, it impacted their motivation to learn and their relationships with staff. Students also revealed they saw pronunciation of names as an issue of respect, equality, and inclusivity, and appreciated any efforts to try to say their name correctly.