A man and his wife entered a deli together late one afternoon. They were the only customers in the place. “May I help you?” asks the server behind the counter. Before either can reply, the other person behind the deli counter, standing off to the side, uttered a fairly loud “uh-hum.” A discussion then took place between the two employees.

Finally, the server turns to the customers and pointing to a ticket dispenser, says. “I’m sorry, but you’ll have to take a number.” The husband pulls #94. The digital sign on the back wall reads 87.

“88,” says the server, behind the counter, “89, 90,”

“This is insane,” says the wife. “91,” continues the server, “92, 93, 94.” At that point, the husband and wife look at each other in disbelief. The wife turns to the server and says, “Sorry, we just lost our appetites, we’ll buy our corned beef and salami elsewhere.”

After the couple leaves, the server goes back to the other person behind the counter, her boss, and asks, “Now wasn’t that a bit stupid? We just lost a good sale?

“Stupid or not,” her boss replies, “That’s the way we do things around here.”

Until you understand what culture is and how it is driving your business the wrong way, learning how to change it to significantly improve results will be challenging. Why? Because the old, “Stupid or not, that’s the way we do things around here” will just keep re-emerging.

And, to be clear, by results, I mean results as measured by your customers through your company’s products or services. Not simply products delivered, systems installed, or services provided, but business results — needs met, problems solved, and goals achieved.

Culture dictates competitive advantage

The power of culture and an incisive plan to manage it is well stated by Jack Welch.

Look, its Management 101 to say that the best competitive weapon a company can possess is a strong culture. But the devil is in the details of execution. And if you don’t get it right, it’s the devil to pay.

Adam Zuckerman, a consultant in Towers Watson’s Chicago office, shows how culture drives marketplace success:

There is growing recognition of the fact among business leaders [that a strong culture drives competitive advantages]. The reality is that culture is one of very few truly sustainable competitive advantages. Companies win not because of what they do, but because of how they do it. And how they do it is determined by culture.

My favorite statement regarding the power of culture on business performance and competitiveness is the oft-quoted organization effectiveness maxim that says:

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

You can have a good strategy in place, but if you don’t have the culture and the enabling systems that allow you to successfully implement that strategy, the culture of the organization will defeat the strategy.

Finally, a November 2015 study, “How Corporate Culture Affects the Bottom Line,” by Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business adds weight to the point that corporate culture is an essential element of business success driving profitability, acquisition decisions, and even whether employees behave in ethical ways.

Executives overwhelmingly indicated that an effective corporate culture is essential for a company to thrive in the modern business world. Among the findings:

- More than 90% said that culture was important at their firms.

- 92% said they believed improving their firm’s corporate culture would improve the value of the company.

- More than 50% said corporate culture influences productivity, creativity, profitability, firm value and growth rates.

- Only 15% said their firm’s corporate culture was where it needed to be.

A snapshot of culture

In my Mining Group Gold and my Building Team Power workshops, I have posed this question to participants: “What does organizational culture mean to you?” This synthesized definition has emerged over time from the many inputs:

Organizational culture is the integrated sum total of all the formally and informally learned and shared assumptions, values, and beliefs, which governs how people behave in organizations. Culture is habitually implied, not expressly defined, yet it has a profound influence on the people in the organization and shapes how they go about their business of working.

Or as more cryptically stated in our opening story: Culture is how we consistently do things around here.

Think of culture as the software that drives how an organization operates. It is the billions of zeros and ones that comprise the code that defines the organization’s basic personality, the essence of how its people interact and work.

Culture operates on both a conscious and unconscious level. It is dynamic and fluid; it is never static. Culture can’t be copied or easily pinned down. Corporate cultures are constantly self-renewing and slowly evolving. The culture that was effective 10 years ago under a given set of circumstances may be out of touch and ineffective today. There is no generically good culture.

What works for your operation in your market may be a disaster for a different organization in another market.

Three intertwined culture drivers

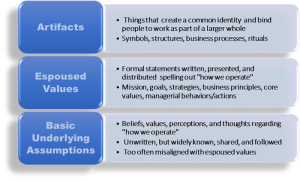

Edgar Schein’s seminal research is pretty clear that three highly interconnected factors are the primary drivers of an organization’s culture. Artifacts give you the first impressions of an organization’s culture. Certainly, words espousing values and beliefs about how we operate around here are important in providing the formal benchmark for the stated culture. But far more important are the deep-seated visible behaviors that are widely shared and practiced day-in-and-day-out.

Let’s examine the three drivers

1. Basic underlying assumptions

These are the underpinning of any culture; the ultimate source of values and actions that move the organization. These basic, underlying assumptions are not written down, but they are widely known, shared, ingrained, and followed by the majority of employees.

These are the powerful unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings that people have come to observe, recognize, and adopt as “the real way to work and succeed here.” They most likely have been around a long time, have survived many “administrations” and directly impact the emergent culture.

The following employee quotes will demonstrate how basic underlying assumptions drive behavior and culture:

“Even though the senior team screams that the customer is #1, we all know that revenue and profit numbers rule in this company because that is what determines our bonus. So, make your numbers any way you can because highly bonused people get the promotions.”

“Collaboration is touted as one of our core values, but you rarely see it. Direct force predominates. But indirect force for getting cooperation when you lack direct authority over people is also used. That process means bullying people to go along by bringing up the name of a big boss and then asserting that he/she expects the stated results to be achieved with everyone’s full participation. We all know that autocratic leadership is our true core value, not collaboration.”

2. Espoused Values

These are the formal statements espoused by the senior leadership team to all employees. They are usually written down in small pamphlets, laminated wallet cards, or slick PowerPoint slides. These espoused values are distributed to all employees. Once distributed, whether or not the senior leadership team ever references them again — in speeches, videos, all-hands communication meetings — varies widely among organizations. Espoused Values typically fall within six areas:

- Mission — What is our reason for existing?

- Goals: — What we intend to accomplish?

- Strategies — How do we intend to accomplish these goals?

- Business Principles — What principles do we stand for to drive our business?

- Core Values –– What values do we hold dear and recognize?

- Managerial Behaviors/Actions — What are expected ways of behaving and relating?

3. Artifacts

Four highly visible elements fall under the artifacts heading: Symbols, Structures, Processes and Rituals. All four are aimed at helping to give people a common identity, to bind them and organize them together as part of a larger whole. Artifacts typically give people their first impression of an organization’s culture and too often are the only factors considered when trying to change the culture.

Symbols: Corporate logos — Apple’s partially bitten apple, McDonald’s golden arches, Nike’s swoosh, Goodyear’s winged foot — not only are ways to build a brand, they act as a common cultural identity for all employees. Plus, in the era of the smartphone, logos are more than a visual symbol, they are the icons that people touch dozens of times a day — and shame to any firm that angers its customers by making a misguided attempt to change that icon.

Architecture, decor, company cars, windowed offices, and titles are highly visible cultural symbols. As are symbols of “winning” like awarding a Rolex watch to a high achiever, or symbols of “equalization” by eliminating all offices and having all managers, including the president, reside in an open landscape.

Symbols emphasizing collaboration and creativity can be shown by having table and chair clusters in a large atrium for small collaborative meetings, having whiteboards all around, and having several high-tech video/audio conference rooms available for long distance meetings.

These are just some ways symbols visually signify and solidify a corporate culture.

Structures: Every organization must have an organizational structure. What structural elements are set in place — rigid vs. flexible work specialization, integrated vs. isolated departmentalization, hierarchical vs. flat chain-of-command, broad vs. narrow span-of-control, stringent vs. flexible job descriptions, etc. — and how these structures are managed, help shape the culture within an organization.

Processes: What management pays attention to and rewards, who it recruits and hires, the image it creates through its multimedia advertising processes, the quality of the customer service and support systems it has in place are just a few examples of powerful processes that shape culture.

Rituals: These are formal and informal ceremonies that are part of the organizational “work-a-day” world. Annual kick-offs, President’s Club trip for top salespeople, service award ceremonies, often retold stories of company history that turn into myths, cake and ice cream on an employee’s birthday, company picnics, organized volunteer projects are typical rituals that help set a culture.

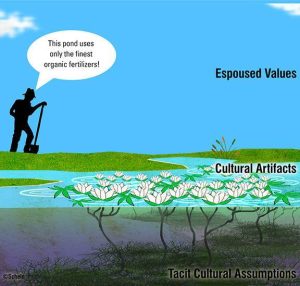

In some of Schein’s recent work, you may appreciate his lily pond analogy shown here portraying the way in which the components of culture operate at different levels of depth and awareness in a state of movement, as opposed to the rigid state of an iceberg; and his interview covering various aspects of culture change.

The issue of misalignment

Here are a few examples that portray how disconnects can occur among the three cultural drivers.

- Basic underlying assumptions— “Be fast, be cost-effective, and if quality has to take a hit so be it” is in conflict with Espoused Values: “We believe in providing the highest quality in both customer and product service, which will gain trust over time.”

- Basic underlying assumptions — “We live in an ‘I’ culture purely based on individual performance”does not align properly to reinforce and facilitate success of a visible Artifact: “Our highly respected, first-class talent development organization uses state-of-the-art tools and processes to teach teamwork and collaboration.”

- Espoused Values — “We expect all teammates to think and act in an entrepreneurial manner, like owners this business”contradicts a known Artifact: An organizational structure that is very hierarchical with centralized decision making.

You certainly will have cultural problems that cripple your business if any of the three intertwined drivers are misaligned.

On the other hand, even if these three are all aligned, but the whole is not producing an effective, competitive company, a planned cultural change is in order.

Some lessons about change

People will fight to protect the status quo — even one they don’t like — because, at least, they understand it and know how to cope with it. Therefore, in attempting to change culture, it is important to remember you are attacking the most entrenched and stable part of your organization; and, the defenders of the current condition can be legion.

Changing behaviors is the most powerful determinant of real cultural change.

What people actually do matters more than what they say. Therefore, to obtain more positive influences from your cultural situation, it is better to focus on changing behavior, which can lead to real culture change. Direct appeals to change beliefs, values, or ways of doing things rarely achieve the desired results, but if behaviors are changed the mindsets will follow.

There are a number of ways to prompt behavioral change to lead to changes in the organization’s culture:

- Hiring new people that “fit” the new culture.

- Giving recognition to practitioners of new culture tools/methods.

- Providing monetary incentives to practitioners of new culture tools/methods.

- Role-modeling by managers of new culture values/philosophy/tools/processes.

- Dismissing those digging in to maintain the status quo of the old culture.

- Promoting opinion leaders who demonstrate new culture desired behaviors.

Internalization of a cultural change — where people embrace the new behaviors and work methods by choice because it makes more sense than the old alternative behaviors — will determine the lasting power of the cultural change being undertaken.

Just doing the “same old, same old” by changing organizational structures, work processes, decision rights, policies, etc. without any thoughtful plan to account for needed behavioral changes that will, over time, bring about an alignment of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs with the behaviors just won’t cut it. All you will get is what the organization effectiveness experts call “change fatigue.”

Communication among people at all levels anesthetized by “change fatigue” goes something like this: “Here comes another ice cream flavor of the month from on high, but, if we just hunker down for a bit, we’ll soon be back to business as usual.”

An old saying captures this point: “The more things change, the more they remain the same.” That is, there can be any number of changes (moving from structure A to structure B, changing from work process A to work process B, etc.) but unless there are accompanying transitions to new behaviors, the culture will remain the same once the dust clears.

Schein, in his outstanding book, Corporate Culture Survival Guide, underscores why so many organizations fail to pull-off a desired culture change:

. . employees wish there were more teamwork, more trust among employees, and so on. However, examining the artifacts typically shows reward-and-incentive systems that put a premium on individual accomplishment and competition among employees for the scarce promotional opportunities that are available. If the company really wants to become team-based, it has to replace those individualistic systems that have worked in the past and are deeply embedded in people’s thinking. If it cannot or will not do that, the end result could be a decrease in morale as employees discover what they hoped for is not happening.

We can espouse teamwork, openness of communications, empowered employees who make responsible decisions, high levels of trust, and consensus-based decision making in flat and lean organizations until we are blue in the face. But the harsh reality is that in most corporate cultures these practices don’t exist because the cultures were built on deep assumptions of hierarchy, tight controls, managerial prerogatives, limited communication to employees, and the assumption that management and employees are basically in conflict anyway—a truth symbolized by the presence of unions, grievance procedures, the right to strike, and other artifacts that tell us what the cultural assumptions really are. These assumptions are likely to be deeply embedded and do not change just because a new management group [or even the current one] announces a new culture.

In summary

As you recognize that culture matters because for better or worse it rules your organization, you begin to see that working on your culture is not an HR topic. Quite the opposite—it’s a financial and strategic topic. In fact, it’s one of the most important things you can do to create a sustainable competitive advantage. And what’s more critical to your organization’s future survival and growth than that?

If you enjoyed this perspective on organizational culture, I invite you to continue with my series here.

This article was originally published on Culture University.