Barely a week goes by without at least one article or study bemoaning the things managers don’t know or do.

A frequent target: the pitifully low level of workplace feedback.

Feedback is “too rare,” “too vague” or too “attaboy.” Its weakness or absence is considered demoralizing, demotivating and devastating to the workforce – a serious disengager.

Not surprisingly, many well-intended articles are brimming with common sense suggestions. Predictable lists dissect when, where and how to give feedback, and the many ways unenlightened managers can begin to do the right thing in the right way.

Change can be taught, but habits are different

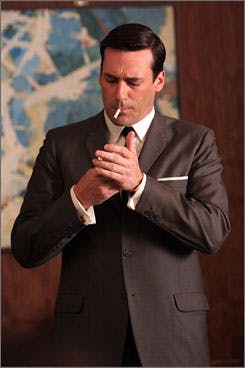

The problem with this avalanche of advice is simple and deep: the widespread managerial practice of not giving people ongoing guidance, direction, and support has become so deeply engrained and ubiquitous a habit that it resembles smoking in the workplace a decade or two ago.

While smoking was a pervasive presence and feedback resembles a corrosive absence, both produce a toxic environment. The haze of smoke and the haziness of manager silence were not created by a shortage of information or warnings – or blog posts. They were created and sustained by millions of individual behaviors taken, or not taken, again and again despite their actual, known and chronicled downsides.

To varying degrees, people knew better. They could read but did not heed the warnings. They were simply the victims of bad habits.

Nicotine drove or reinforced the smoking habit. Perhaps the norms of organizational success are the equivalent substance driving silence where commentary should flourish. After all, similar environmental factors support both harmful habits.

1. The habits seem nearly universal

When everyone does it (ashtrays abound) or few if any do it (feedback is seldom heard), a powerful but unspoken norm exists. Subtle or pervasive social pressure may reinforce the norm.

As a critical manager once told me in a focus group, “Here we believe that real men don’t give feedback – or need it.”

There are exceptions to any rule in a workplace. There were always non-smokers and there were always those giving good feedback – but they were far less visible.

2. Winners credit the norms for their success

Most would-be and existing managers believe that you move toward the top by emulating the dominant standards and habits (the so-called culture) of the organization.

If you’ve moved up often and survived a couple of decades receiving or giving little or no feedback, it might seem to be a factor in your success. There’s certainly little percentage in randomly putting out cigarettes or publicly and regularly providing praise and direction.

3. Habits trump warning labels

The most instructive piece of the smoking analogy is the famous and long-running Surgeon General mini-post on each pack: “Cigarette smoking may be hazardous to your health.”

For two decades this instruction was the backdrop to increasingly intensive and comprehensive efforts to contain and reduce smoking. This memorable backdrop was widely viewed as largely ineffective itself in actually changing “The Habit”.

And so it may be with our avalanche of guides to good managerial behavior. They are an important, but ultimately, a largely ineffective step in changing the decades-old habit of studied silence that is clearly hazardous to individual and organizational health.

Any managerial wellness program should include this most basic behavior modification as just that: part of an intentional and systematic initiative to modify core behaviors.

My firm learned in a multi-year, 16-hospital team self-scheduling project in New York City the limits of change by proclamation. Dysfunctional habits, including the widespread withholding of feedback in these rigid and unionized environments, had to be changed for collaborative scheduling to occur.

What we called the Mutual Respect skills only took hold when serious behavior modification (long-term interactive training + support) occurred.

Without reinforcement, change is a longshot

Unfortunately, there is no “patch” to reinforce good managerial habits.

But there are compelling reasons for organizations to intensify the prevalence of feedback and other habits like providing direction for development, useful performance information between reviews and coaching. These can be low-cost, high-impact changes, but they require ongoing and thorough support, such as:

- Mandate a non-smoking (or feedback intensive) workplace. Hazards can and should be outlawed as a matter of policy. Absent such a declaration and the implementation steps below, tens of millions of employees will be the victims of first-hand and second-hand indifference. Engagement will suffer.

- Set standards for quality, quantity of feedback. To declare there should be more and better feedback is meaningless. In many workplaces, today’s standard would be: 0 feedback to all employees in a six-month period. Consider setting a simple Year 1 mandate: one (1) piece of feedback to each employee weekly. Sounds like quite a change. But a no smoking office has no smoking ever by everyone – quite a change indeed. Proposing such metrics would be a lively discussion – but one that is long overdue. And the standard could be raised over time

- Create effective, long-term training and supports. The difference between habitually urging change and decisively changing behavior is substantial. It resembles the difference between much corporate education and Marine training. One hopes for impact and the other insists that lasting and predictable behavioral change occur. If old habits – such as never giving feedback – are accepted, rewarded and comfortable, modifying them requires at least:

- Intensive behavioral training with follow-on reinforcement sessions that undoes old assumptions, introduces systematic goals for giving feedback, breaks down resistance and reinforces success.

- Quarterly assessment of behavior change progress against goals based on 360° feedback. Retraining can be provided as needed.

- Commitment to an ongoing campaign to maintain a “smoke-free” or feedback rich environment, maintaining a commitment to standards and exploring ways to strengthen an appreciative culture.

Hasn’t the time come to move beyond describing toxic environments and the voluntary steps that might clean them up?

If there were a Manager General, he or she would probably have moved beyond warning labels by now.