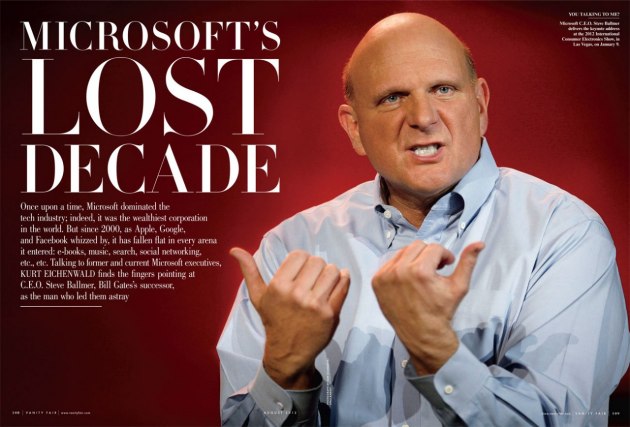

This one cannot be blamed on HR but on a current August 2012 Vanity Fair article — How Microsoft Lost Its Mojo — that argues that the performance appraisal practice known as “stack ranking” or forced distribution “effectively crippled Microsoft’s ability to innovate.”

According to the author, Kurt Eichenwald,

Every current and former Microsoft employee I interviewed — every one — cited stack ranking as the most destructive process inside of Microsoft, something that drove out untold numbers of employees … It leads to employees focusing on competing with each other rather than competing with other companies.”

Adopting a Jack Welch idea

GE and its former CEO Jack Welch are credited with introducing the idea (also known as forced ranking) over a decade ago. I also read several years ago that they had shifted to a variation on the original idea after they realized it is not a viable long term practice. I have not seen recent broad-based surveys showing how widely the practice is used, but I have to guess any ideas associated with Welch sounds great to corporate leaders.

Microsoft was for years one of the few companies that had a better track record than GE. I would have guessed they have an army of innovative people. “Outing” their problems should trigger a badly needed discussion.

It’s important for employers to identify their stars and their “turkeys.” I’ve made that argument in several blogs and articles. Recent reports suggest it is even more important today.

But stacked ranking is an answer to a specific problem – rating inflation and the failure to differentiate. If we relied on performance criteria that made it easier for managers to explain and defend year-end ratings, there would be no need to force managers to differentiate. I suspect the practice was triggered by Jack Welch’s frustration with obviously inflated ratings.

But stacked ranking is an answer to a specific problem – rating inflation and the failure to differentiate. If we relied on performance criteria that made it easier for managers to explain and defend year-end ratings, there would be no need to force managers to differentiate. I suspect the practice was triggered by Jack Welch’s frustration with obviously inflated ratings.

Obvious legal pitfalls

There are all too apparent problems with the way employee performance is planned, managed and evaluated by managers. Critics going back decades have called for the eliminating of performance appraisals. As staunchly as I (and others) defend the practice, the critics have completely valid concerns.

One of the most vocal critics was Dr. W. Edwards Deming, the TQM (total quality management) guru, who made the point – one of several to support his criticism – that two managers could easily disagree on how to rate an employee’s performance, with one rating someone as a “4,” for example, and the second rating the same person as a “3.”

That happens more often than we are willing to acknowledge. Deming argued that is evidence that ratings and the use of rating scales are invalid – and he was correct. It’s a problem that has rarely been studied but could be universal. Employers should be thankful ratings are rarely scrutinized in court.

Companies are correct, in my opinion, in shifting to three-level rating levels, focusing on the high and low performers – the “1s” and “3s” — and assuming the majority of employees are “2s” and “doing their jobs.” Research shows that the stars and the turkeys stand out, and that co-workers know and often agree on how many is in each group.

Further, in the typical work group, roughly 20 percent are seen as stars, which is consistent with the typical forced distribution policy but – and here is a key issue – the employees whose performance is inadequate is not as high as 10 percent. No research supports that; it’s arbitrary.

A system nearly impossible to defend

Now stacked ranking takes admittedly shaky ratings and tries to integrate the ratings from multiple managers into a list showing where employees stand in a forced distribution. Those decisions cannot be defended based on the information in the typical personnel file.

Evidence from other similar situations – job evaluation committees are an example – shows the ability of managers to articulate and defend their views as well as the political stature of a manager influences the group’s decisions. An added problem is the scarcity of factual evidence relevant to employee performance and the widely recognized inability to “measure” performance for many jobs. All of which makes the forced ranking impossible to defend.

But then the problem is compounded by the completely indefensible idea of initiating actions adverse to an employee’s career for those in the bottom 10 percent — and to do that year after year. Simple logic says very clearly that it will only take a few years before the bottom group includes a lot of employees who in prior years were rated as a “2” — good people whose careers will now be ruined.

Furthermore, there is always – always – the potential for discrimination, be it age, gender, or you name it. If I was a lawyer, I would go from company to company and have people looking for those former employees terminated because they fell into the bottom 10 percent..

Distorting the purpose of annual appraisals

One of the perpetual issues with performance appraisals is the dual purpose – to provide feedback employees need to improve performance, and, to support personnel actions. Both, in concept, are focused on individual employees, their capabilities, their careers, and their commitment to job performance.

The focus is and has to be on the discussions of those issues between managers and their people. Ideally managers need to be able to have open, honest discussions.

Using ratings to compare one employee with another is inevitable for individual managers who have to allocate salary increase dollars. That’s been a point of criticism in numerous books and articles. It’s inevitable in a pay-for-performance environment.

But, making career altering decisions based on the different perceptions of managers who have no direct knowledge of the work or workers in other work groups, and especially where those groups involve different occupations, is a distortion of the textbook appraisal concept.

This is a broader problem, but our performance systems would be more credible, easier to defend, and more effective tools for managers if the performance criteria were job or occupation specific.

If, for example, we want to help a carpenter improve, then we need to understand the skills and abilities relevant to being a highly successful carpenter. We would never consider using the same criteria with a plumber or painter. I have a similar reaction to comparing an HR manager with a marketing manager. The focus is properly on how well each is performing his or her

Teamwork a key to continued success

Our professional sports teams prove an organization can have rigorous performance management practices, including significant pay disparities, and still reach high levels of organizational success. They focus on how well each player performs the requirements for his or her position.

Coaches focus on improving “job” skills. Significantly, players are recognized for outstanding performance but even the very best are sometimes overlooked if they play for an unsuccessful team.

Competition does contribute to better performance. That’s well established. It’s frequently adopted to motivate sales. Studies in companies with stacked ranking show performance improves initially.

But this competition is not over a few extra salary increase dollars or the relative size of a bonus. Moreover, winning and losing rides more on their manager than on their actual performance. After the few truly poor performers are jettisoned, the practice inevitably will become counterproductive.