Having a sponsor at work can accelerate your career, but not everyone has someone who will go to the mat for them. While having a sponsor pays a premium, the size of that boost depends on who your sponsor is.

Last year as part of our ongoing inclusion, diversity and equity efforts, PayScale implemented a sponsorship program. The program paired lower-level or newly hired employees, called protégés, with more senior people, called sponsors, who could actively help promote the protégé’s career.

Lilyanna and Karaka are two PayScalers who opted to participate in the program. Lilyanna was a relatively new hire in the finance department. Karaka had been at PayScale for 10 years and was a director on the product team. On the surface, they may not have seemed to have much in common. Lilyanna is a numbers person who tends to be a bit introverted. Karaka is a big-picture person who is as comfortable presenting to 300 people as she is talking to one. Over the next several months, they met every other week and discovered they had far more in common than one would think by just looking at the surface. They are both focused, hardworking and incredibly smart people.

At some point, Lilyanna had the opportunity to work on a major product strategy initiative. It was a bit of a stretch for her, but Karaka encouraged her, reviewed her work and gave her pointers. Lilyanna’s success with that project became one factor that led to her promotion. Afterward, she was given other assignments working to bring together the finance and product teams. Karaka helped her by introducing her to people and highlighting areas where she could fill a void. Today, Lilyanna plays a vital role working across the product and finance teams at PayScale and she got promoted again. This all happened in less than a year.

The difference between mentors and sponsors

“Get a mentor” has long been standard advice for students and young professionals. The benefits of having a mentor range from having someone who can lend a sympathetic ear to having someone who can help map out your career. In turn, these can translate into career growth.

In recent years, however, the conversation regarding career allies has shifted from the benefits of having mentors to the advantages of having sponsors. The key difference between mentors and sponsors is that mentors give advice while sponsors actively seek to provide opportunities. Mentors can be akin to career coaches that help their mentees navigate difficult situations. They are usually more seasoned professionals, but they do not have to be in the same organization as their mentee. Sponsors, however, are decision makers within a protégé’s organization and are often in the protégé’s reporting chain. They ensure their protégé is selected for prime assignments, gets promotions and receives pay increases.

Karaka and Lilyanna’s relationship is a good example of a sponsor and protégé. At the start of their relationship, Karaka was an influential person at PayScale. Lilyanna, on the other hand, had concrete goals she wanted to accomplish but wasn’t sure how to navigate working towards them. Because of her seniority and tenure at PayScale, Karaka was able to not just advise Lilyanna, but to actively aid her in meeting her goals.

For women, particularly women of color, having someone in a position of power who will go to the mat for you can be an effective way to combat systemic bias and break through the glass ceiling to positions of power and higher pay. When choice assignments or opportunities for promotion come up, a sponsor can put forward their protégé and, since sponsors have clout and are in a position of authority, others will give their protégé opportunities they might not have otherwise.

∼∼∼∼∼

In this article, based on PayScale survey data, we examine who has workplace sponsors, the characteristics of sponsors and the benefits of sponsorship. We find that while men and women report roughly equal rates of having a sponsor, women’s sponsorship rates vary greatly by race/ethnicity. Black or African American and Hispanic women have the lowest rates of reporting that they have someone who is advocating for them within their organizations.

Using PayScale’s salary survey, we also investigate whether it pays to have a sponsor. We find that there is a “Sponsorship Premium,” however, the boost to your salary varies depending on who your sponsor is. Protégés who have male and/or white sponsors have larger sponsorship premiums. Here too, we find that women of color are at a disadvantage since they have higher rates of reporting that their sponsor is a woman and non-white.

Women of color face many unique challenges in the workplace. Having a mentor who can relate to those difficulties and who can help navigate them has its benefits. However, mentorship and sponsorship in the workplace aren’t the same thing. While you may seek a mentor of your same race/ethnicity and sex, having a white man as your sponsor can really pay off.

Who has a sponsor

Between December 2018 and May 2019, over 98,000 respondents to our salary survey were asked about their current position and salary. In addition, they were asked if they had someone who is advocating for them within their organization. If they answered yes, they were asked about that person’s role, gender and race/ethnicity. (In the survey question, we used “advocating” since “sponsoring” could easily be confused with sponsoring a work visa.)

Overall, 56.7% of respondents said they had a sponsor. When we look at the data by gender, the numbers do not change greatly. Roughly 57.4% of men said they have a sponsor, while 56.0% of women did.

(This finding is at odds with those of others who find that women are less likely to have a sponsor than men. While this report is based on a far larger sample, the other findings are based on more detailed surveys and interviews. These differences likely account for some of the differences our findings.)

Our data by race/ethnicity shows that there are some large differences between groups. For most groups, at least 60% of those surveyed said they have an advocate at work. However, only 55% of black and Hispanic women reported having a sponsor. For comparison, 62.5% of white men reported having an advocate in the workplace. Since our data tends to over-represent white-collar workers, we limited this sample to workers with at least a bachelor’s degree (see methodology for more details.) Workers with lower levels of education may have different sponsorship patterns.

The sponsorship premium

These large differences in sponsorship are important because those who report having a sponsor also tend to be paid more. In other words, there is a sponsorship premium. Overall, those who have a sponsor are paid 11.6% more than those who do not. For men, the sponsorship premium is even higher: 12.3%. For women it is 10.2%.

When we control for various compensable factors such job title, education, location, etc., the sponsorship premium shrinks but is still notable. We call this the controlled sponsorship premium, and it is 2%. In other words, those with a sponsor earn 2% more than similarly qualified people without one. The sponsorship premium remains larger for men than women even after controlling for other compensable factors: 2.3% for men and 1.7% for women.

The premium varies by race/ethnicity

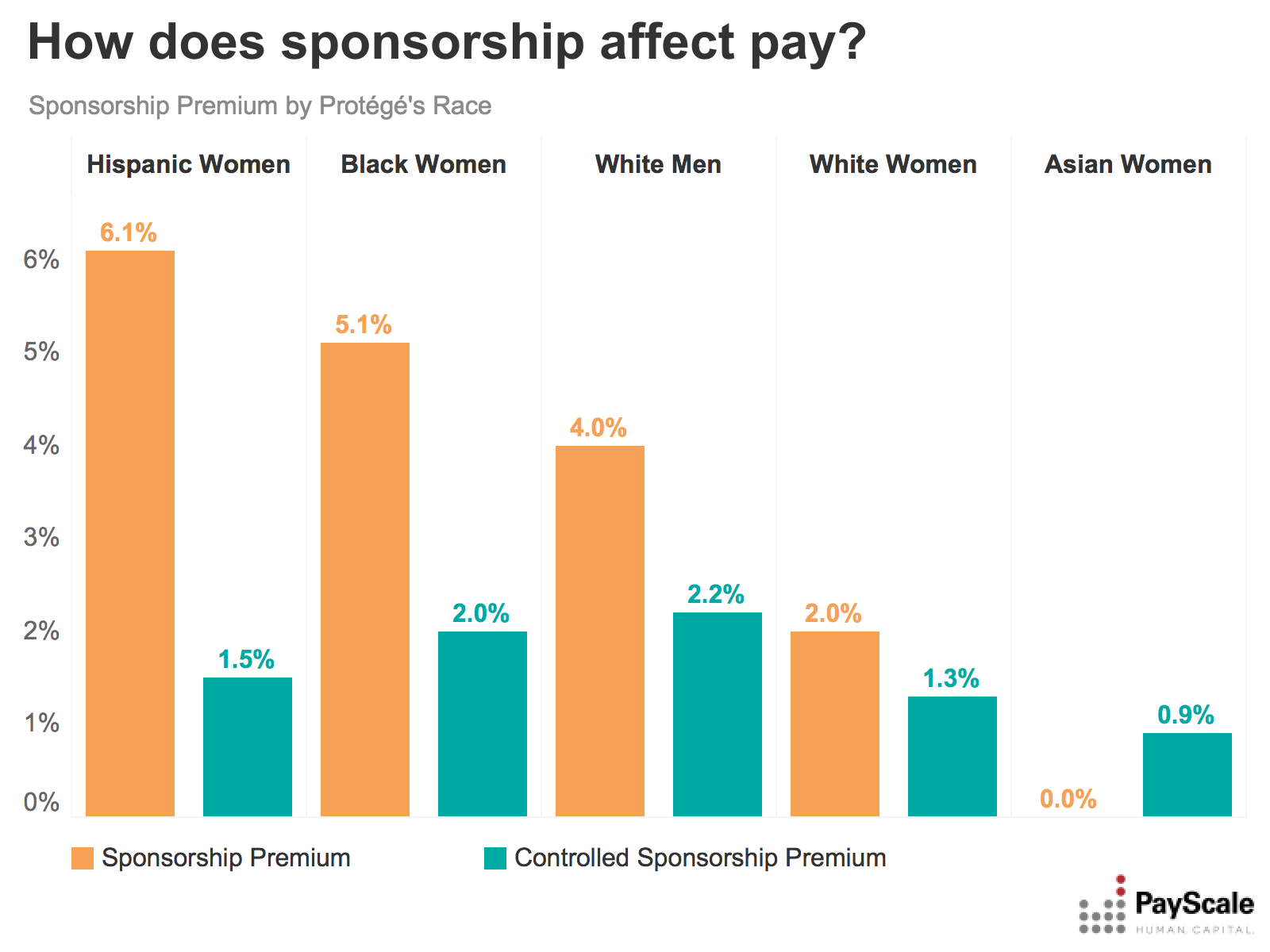

The data by race/ethnicity, which is restricted to those with at least a bachelor’s degree, suggest that Hispanic and black women have the most to gain from sponsorship. Hispanic women with a sponsor earn 6.1% more than Hispanic women without one. Black women with a sponsor earn 5.1% more than black women without one. On the other hand, Asian women with a sponsor earn about the same as those without one. For comparison, the sponsorship premium for white men is 4%, while for white women it is 2%.

The controlled sponsorship premium does not follow the same pattern. When we control for various compensable factors, the sponsorship premium is largest for white men. Their controlled sponsorship premium is 2.2%, meaning that white men with a sponsor make 2.2% more than similarly qualified white men without a sponsor. Black women have the next highest controlled sponsorship premium at 2%, followed by Hispanic women at 1.5% and white women at 1.3%. For Asian women, the controlled impact on pay of having a sponsor is slightly positive. Asian women with a sponsor earn 0.9% more than Asian women without one.

We are unable to pinpoint why Asian women seem to benefit less from having a sponsor than women of other groups. One potential explanation is that Asian women tend have small or positive wage gaps relative to white men and so may see less of a monetary benefit from having a sponsor than women of other groups. Another potential issue is that the group “Asian” includes people from various ethnicities that are not treated equally in the workplace. It could be that some Asian ethnic groups that tend to face more challenges in the workplace benefit more than others but we are unable to capture this. Further quantitative and qualitative studies could help uncover why sponsorship does not seem to benefit Asian women like other groups.

Benefits beyond pay

The benefits of having a sponsor can go beyond pay. When we look at the data by job level, those higher up the corporate ladder tend to have higher rates of sponsorship. 55% of individual contributors (i.e. those who do not manage others) say they have a sponsor. Each step up the organizational ladder sees an increase in sponsorship: 59.2% of managers, 63.1% of directors and 65.5% of executives say they have a workplace sponsor.

While we are unable to directly measure the impact of having a sponsor on job level, our data complement other research that shows sponsorship accelerates your career.

Economist Sylvia Ann Hewlett finds that entry-level people who have a sponsor are 167% more likely to have gotten a stretch assignment. Researchers Herminia Ibarra, Nancy Carter and Christine Silva find that sponsorship leads to promotions.

Both of these findings were true for Lilyanna. Karaka, her sponsor, pointed out an opportunity for her to work on something that was beyond what she had been doing. Lilyanna’s success in that stretch assignment contributed to her promotion and led to more complex and strategic projects. Her success on these projects, in turn, led to an additional promotion.

Who sponsors whom?

Sponsors typically sponsor those in their own reporting chains. Nearly three-fourths of all respondents who say they have an advocate say that their direct manager is their sponsor, while an additional 16.3% of protégés said that their manager’s manager was their sponsor. Only 10.5% said it was someone outside their department.

For the most part, this trend is consistent across demographics. Over 70% of protégés in each demographic group we looked at said that their direct manager was their sponsor, with the exception of black women. Only 68.3% of black women who are protégés said that their direct manager was their sponsor. Black women, however, had higher rates of saying that their manager’s manager was their sponsor – 20.3% of protégés selected this option.

Protégés’ gender is typically the same as their sponsor. Overall, 57.4% of protégés who reported their sponsor’s gender said that they were a man. However, 77.1% of male protégés said they had a male sponsor while only 40.4% of female protégés reported the same.

Race/ethnicity also tends to match between sponsors and their protégés. Over 90% of white men and women protégés who reported the race/ethnicity of their sponsor said that they were also white. Women protégés of other racial/ethnic groups were far less likely to report that their sponsor was white. Just over half of black and Hispanic women protégés reported having white sponsors: 58.8% and 59.4% respectively.

Having a white male sponsor pays

It is clear from our research that who your sponsor is impacts the sponsorship premium. Sponsorship increases pay for all groups but having a white man as a sponsor tends to lead to the largest pay increases.

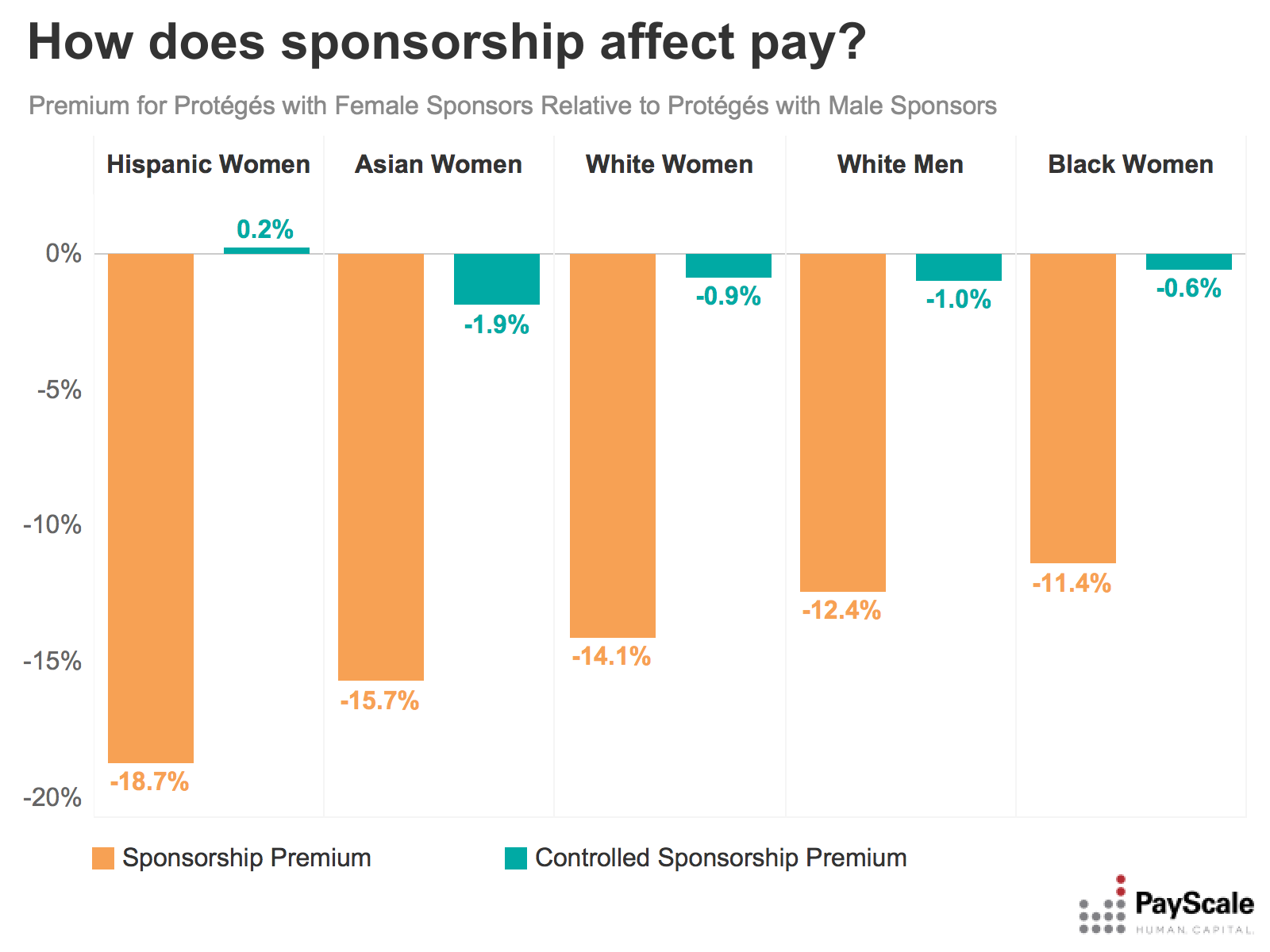

Female protégés with a woman sponsor earn 14.6% less than women who have a male sponsor. When we control for various compensable factors, female protégés with female sponsors still earn 0.7% less.

The benefit of having a male sponsor is not limited to women though. Male protégés who have a female sponsor earn 8.7% less than male protégés whose sponsors are men. After controlling for various compensable factors, men with female sponsors make 1% less than similarly qualified men whose sponsors are men.

Women of color who have a person of the same race/ethnicity as their sponsor benefit far less than those who have someone who is white. Hispanic female protégés with Hispanic sponsors make 15.5% less than Hispanic women with white sponsors. After controlling for various compensable factors, this shrinks to 2.1%, but the gap remains. Black female protégés who have black sponsors make 11.3% less than those who have white sponsors. After controlling for various compensable factors, this shrinks to 1.2%. Finally, Asian female protégés with Asian sponsors earn 1.4% less than those with white sponsors. When we control for compensable factors, Asian women with Asian sponsors make 1.7% less than those with white sponsors.

In some respects, it is not surprising that those who have white men as sponsors tend to see more financial rewards than those who have women and/or people of color as sponsors. Research has shown that there are more men named “John” in top executive positions than there are women in executive positions in general. People of color are similarly few and far between in the upper echelon of society. Even when they do make it to the top, gender and racial pay gaps persist.

Research also shows that women and minorities that advocate for other women and minorities are penalized with worse performance reviews. Given this and other obstacles that women and/or people of color face in the workplace, it is not surprising that protégés sponsored by white men have the highest sponsorship premiums.

Be a sponsor

Our data shows that those who have a sponsor make more than those who don’t. However, who your sponsor is impacts how much of a benefit you will see. Those who have white men as sponsors tend to make the most.

For junior-level women and people of color, having a mentor of your same gender or race/ethnicity who can relate to the obstacles you face in the workplace is invaluable. They can be a sympathetic ear who knows how the “innocent” comment made by a colleague was a microaggression. They can relate to being the only woman and/or non-white person at the table. However, when it comes to sponsorship, i.e. having a higher-up at your organization that will go to the mat for you, there are benefits of having a white man in your corner – namely more money.

Our research also highlights an important way that white male allies can actively start to break down centuries of systemic bias in the workplace. White men can actively seek to sponsor women and people of color in their organizations. This requires actively resisting our natural tendency to gravitate towards others who look like us.

The good news is that you can start by chatting with a junior employee while you’re both getting coffee. As Karaka put it, “It starts with building a relationship, finding something you have in common, and going from there.”

As you build trust in a new workplace relationship, look for ways that you can be more than just a mentor. Can you encourage your protégé to take on a stretch project? Can you vouch for them with a colleague? These acts not only help out a promising junior colleague but also help your organization become a better place to work.